It’s one thing for the National Weather Service to say that tornado damage is caused by dangerous debris hurled at high speeds, and quite another to really understand what that means. The amazing photograph on the left, shot in Pampa, Texas on June 8, 1995, gives you a different level of understanding of that statement. This is about an F-3 or F-4 storm that is plowing through an industrial area behind the residential neighborhood in the foreground. The scale is deceptive; the larger pieces of debris in this photograph are vehicles that were picked up from an oil company parking lot, according to photographer Alan Moller, senior forecaster with the National Weather Service and storm chaser. Video taken of that same funnel by a sheriff on the scene clearly shows pickup trucks and vans airborne at an altitude of 80 to 90 feet off the ground: the height of an 8-story building. It would be hard for statistics to give you the deep understanding of the danger posed by flying debris in a tornado that this single image of airborne crushed vehicles gives you. That is the power of experiential knowing, even when it’s indirect like this.

The most powerful tornadoes are classified as F-5 on the original Fujita Scale. While they make up about 1% of all tornadoes, they account for the vast majority of fatalities because they level most structures. The videoclip linked to the “tornado button” below right was shot on the same day as the photo above, of a larger tornado spawned by the same storm system. It shows the tornado passing perilously close to a prison near Hoover, Texas. The prison is a large structure; look at the windows to get a sense of scale. While there is no way to know the intensity of this tornado (because the F-scale and the newer EF-scale are both based on structural damage and the tornado missed hitting the buildings, and also because the diameter of a funnel is not directly correlated to its windspeed), the videoclip can give you a sense of the power of a tornado in the F-5 class.

Click on the clip above to watch a massive tornado pass close to a prison outside Hoover, Texas on June 8, 1995, starting at the 55 second mark on the video. With thanks to Martin Lisius/Storm Stock, who filmed this video and provided the link for embedding as well as permission to use the clip on this educational page.

You can see from this videoclip that had the tornado struck the prison, it would have destroyed it, or at least caused very severe damage. Again, obtaining a true understanding of the magnitude of an F-5 tornado is extremely difficult in any way except for directly experiencing one — although this is one case where gaining direct experiential knowledge could easily be fatal.

A clip like this might lead you to rethink the things you’ve heard about what to do in the event of a tornado. After all, it seems unlikely that the prisoners would have been safe anywhere in that structure, had the tornado hit the buildings. This kind of re-thinking what you knew before is very positive, as it means you are starting to integrate different ways of knowing to create an understanding that is much more powerful and responsive than simply knowing one or two “safety tips.” That’s the kind of understanding that can save your life in a severe storm.

Before we pursue integrated knowing farther, though, let’s look at some other images that explore the benefits and limitations of experiential knowing more fully, as it applies to tornadoes and trying to survive them.

Because images are so powerful, we tend to believe them. The old adage “seeing is believing” is based on the impact experiential learning has on our overall understanding of things. However, no one kind of learning is sufficient in and of itself to lead to complete understanding, and when we forget that it can lead to tragedy.

Remember the debris that a tornado throws with its high winds? The Pampa, TX tornado photograph at the top of the page can remind you; those larger objects are airborne vehicles, and the smaller items are ripped-apart sheet metal and lumber. Large amounts of flying debris, such as the one in the Pampa, TX photograph, are common in strong and violent tornadoes (those rated F2 or higher).

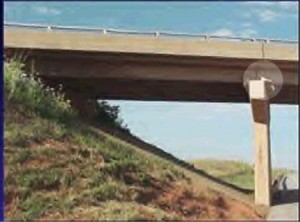

This photograph is one of the overpasses that took a direct hit from the Oklahoma City tornado. One person died here, huddled at the top of the embankment to your left as you look at the picture. The light circle highlights a large piece of sheet metal that the tornado winds embedded in the the concrete overpass support, roughly at the same level above ground where the people were sitting. This is only one piece in a cloud of flying debris that accompanied the tornado winds. These winds, which were in excess of 200 miles per hour, hurled large amounts of flying debris, literally like missiles at those very high wind speeds, beneath the overpass at the people crouching under the bridge – it killed one of them and seriously injured the others. In addition to the threat from flying debris, wind speeds are also higher at the bridge level. The lowest wind speeds in a tornado are directly at ground level, which is why it is generally safest to get as low as possible. A highway overpass is up at the top of an embankment, so wind speeds are higher there than on the ground or in the ditch at the same location.

Some people in Oklahoma City that year were so certain a highway overpass was a safe place of refuge — because they had seen images such as the one of the woman and her children on this page — that that they left their homes and drove to a nearby overpass to seek shelter from the tornado, seriously endangering themselves and others. Many people who remained in their homes in the same neighborhood survived the same storm, sometimes uninjured. The photo to the left shows you an innermost room on a ground floor of an otherwise demolished home. Seven people walked out of it alive, after the Oklahoma City tornado. The reason severe storm experts advise you to go to an innermost room like this is because of the flying debris that we keep mentioning; this wind-driven debris rips away the outermost walls of a structure as the tornado approaches, and the more walls there are between you and the debris, the more likely it is that some walls will be left standing to protect you from it by the time the tornado moves on.

Now you have conflicting experiential evidence about what’s safe. The enormous tornado that threatened the Hoover area in the second videoclip certainly looked like something it would be best to get away from in any way possible. Yet people who went into an inner room in their houses during the Oklahoma City storms survived better than those who drove to overpasses they thought might be safer. Those motorists also caused traffic jams that posed additional, terrifying dangers to others, sometimes blocking highways so thoroughly that even emergency personnel were trapped in their vehicles, unable to help others or themselves. In recent years, information about the dangers of seeking shelter under an overpass has made its way into public awareness and helped stop some of these dangerous highway behaviors. Yet, people who can see an enormous funnel approaching their neighborhood often feel like they might have a better chance of surviving if they escape rather than shelter in place. The dangers and safety trade-offs are so complex in this kind of situation that the National Severe Storms Center has prepared a podcast of information you can listen to here.

As you can see, in a complex situation, any one kind of knowing is not enough to base a decision on.

Continue to Spiritual Ways of Knowing and Learning About Tornadoes.

Return to Experiential Ways of Learning and Knowing.

You may use the table below to explore the directions, their associated ways of knowing and learning, and an example of each type of learning as applied to understanding tornadoes.

People who provided invaluable advice, explanations, images, and editorial assistance to the creation of these pages in 2007, with our thanks.

- Chuck Doswell, NSSL

- Alan Moller, NWS

- Daphne Zaras, NSSL

- Mary Meacham, NSSL

- Kevin Kelleher, NSSL

Any errors that might still exist on these pages are solely the responsibility of Tapestry.