Intellectual knowing is accomplished by the brain through thinking processes such as reasoning, logic, analysis, pattern recognition, and generalization. Ways of knowing and learning generally referred to as rational, analytical, logical, or empirical, and that deal with the observable material world or with highly-developed abstract concepts (such as philosophy or higher mathematics), are included in this category.

Intellectual knowing is accomplished by the brain through thinking processes such as reasoning, logic, analysis, pattern recognition, and generalization. Ways of knowing and learning generally referred to as rational, analytical, logical, or empirical, and that deal with the observable material world or with highly-developed abstract concepts (such as philosophy or higher mathematics), are included in this category.

While brain function is obviously related to intellectual ways of knowing of this type, some of the more important ways that brains process information are far more subtle than what we think of as “reasoning”. Our brains help us process sensory input into perception.

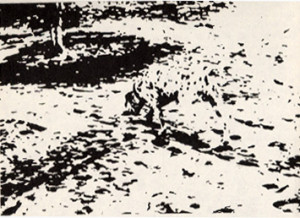

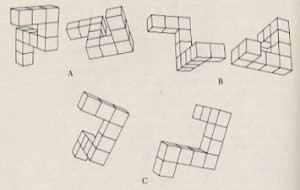

The diagram of black and white splotches to the right has no meaning except that given it by the brain itself. If you look at it a moment, you’ll notice that after a very brief lag time of processing you suddenly “see” the image in the picture. A second picture, below left, shows pairs of objects that are oriented differently in three-dimensional space. If you rotate one or both of the pairs in your mind, you can “match them up” to see if they’re pictures of the same thing. Notice that this process is a bit more difficult and requires more intentional concentration, therefore taking you longer. Also, whereas most people can see the picture in the pattern of black-and-white splotches, the ability to rotate figures in three-dimensional space varies substantially. Some people can do it very easily while others simply can’t.

Howard Gardner’s 1993 book “Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences” (Basic Books) explores the range of human thinking processes and concludes that our culture has been too quick to classify only certain types of brain abilities as “intelligence” for purposes of testing a person’s smartness or possibility of future success. Clinical neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks explores still broader types of non-analytical brain functions that expand our understanding of how the brain participates in many different types of knowing. His best-selling book “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: and Other Clinical Tales” (Touchstone: 1998) challenges our ideas about brain functions, intellect, and intelligence in provocative ways. Nevertheless, “intellectual” knowing as we are typifying it here — the way it is generally typified in American culture — refers primarily to rational, analytical processes. At the same time, Intellectual Ways of Knowing engage all the other ways of knowing through the process of perception. Understanding the role of perception in the process of knowing — whether through art, story, dream or any of the others described — points us to the awareness that all the different ways of knowing are integrated almost seamlessly in real life. The quotes at the top of this page are meant to suggest the same holistic view of human knowing.

To explore an example of Intellectual Ways of Knowing first-hand, visit Intellectual Ways of Learning about Tornadoes.

To proceed around the Circle of Ways of Knowing, visit Experiential Ways of Learning and Knowing.

To proceed around the Circle to the next direction, visit South.

You may use the table below to explore the directions, their associated ways of knowing and learning, and an example of each type of learning as applied to understanding tornadoes.