What do you mean by Indigenous Knowledge?

Indigenous Knowledge may be any of three general types of things. First, it can be a body of information about how to live in a given environment: information about wild foods, traditional agriculture, and herbal medicinals, for example. It also includes the stories, songs, rituals and other types of knowledge that go with and are part of the environmental or ecological knowledge about things such as food and medicine. Second, Indigenous Knowledge (or IK) can be the processes by which people come to know about the natural world and themselves. IK uses many different ways of learning and knowing, and is contextual, relational, and community-based. Finally, Indigenous Knowledge can refer to the source of information, which has its own agency and chooses to reveal itself to humans who approach it in a respectful way.

Why do we need to support Indigenous Knowledge with grants? Aren’t there other ways for people to fund IK projects?

Indigenous Knowledge operates within Indigenous worldview. The two things are parts of a single whole. This does not mean people who work with IK are archaic or locked into historical ways of doing things. A worldview is a way of understanding Reality and relating to it productively, not a specific set of cultural traits or activities. Standard grant opportunities that might seem able to provide funds for IK projects operate within an entirely different worldview, that of the dominant modern culture. This makes sense because it was within this worldview that the system of supporting research with grants originated to begin with. But unfortunately, such grant programs don’t “match” the goals and methods inherent to IK work that’s carried out within Indigenous, rather than Western, worldview. As one small example of the difference, standard grants ask project leaders to identify the outcomes their work will achieve, and evaluation of the grant’s success is based on whether or not those outcomes are achieved. In Indigenous worldview, it’s actually presumptuous and arrogant for a project leader to think s/he can say precisely what will be learned in advance when working with IK. A goal can be envisioned, and a path to achieving that goal can be mapped out, but where that path ends up going is not up to the project leader but to Indigenous Knowledge itself. So there has to be a different set of criteria for evaluating the “success” of a project, especially if funding for subsequent work is solicited by the same project leader. The means of assessment must be framed within Indigenous worldview. Fortunately, there are a number of extraordinarily well-educated and experienced Indigenous scholars who specialize in assessment and evaluation who can help craft appropriate protocols for the new grant program. This is an example of the type of work that will be done in our Planning process.

Indigenous Knowledge operates within Indigenous worldview. The two things are parts of a single whole. This does not mean people who work with IK are archaic or locked into historical ways of doing things. A worldview is a way of understanding Reality and relating to it productively, not a specific set of cultural traits or activities. Standard grant opportunities that might seem able to provide funds for IK projects operate within an entirely different worldview, that of the dominant modern culture. This makes sense because it was within this worldview that the system of supporting research with grants originated to begin with. But unfortunately, such grant programs don’t “match” the goals and methods inherent to IK work that’s carried out within Indigenous, rather than Western, worldview. As one small example of the difference, standard grants ask project leaders to identify the outcomes their work will achieve, and evaluation of the grant’s success is based on whether or not those outcomes are achieved. In Indigenous worldview, it’s actually presumptuous and arrogant for a project leader to think s/he can say precisely what will be learned in advance when working with IK. A goal can be envisioned, and a path to achieving that goal can be mapped out, but where that path ends up going is not up to the project leader but to Indigenous Knowledge itself. So there has to be a different set of criteria for evaluating the “success” of a project, especially if funding for subsequent work is solicited by the same project leader. The means of assessment must be framed within Indigenous worldview. Fortunately, there are a number of extraordinarily well-educated and experienced Indigenous scholars who specialize in assessment and evaluation who can help craft appropriate protocols for the new grant program. This is an example of the type of work that will be done in our Planning process.

What kinds of projects can be supported by the IKhana Fund?

We can’t foresee the range of projects that will germinate, but we can at least identify projects that exist right now for which Indigenous people are having a hard time securing financial support from standard grant sources. Here are three brief examples of things that would be eligible to apply for IKhana Fund support. Many additional kinds of projects are possible.

-

-

- Indigenous graduate students in mainstream universities who are using Indigenous Research Methods in their thesis and dissertation work, who are unable to get support for the parts of their studies that are specifically IK in either process or information, could apply for funding to support the IK portions of their thesis or dissertation work.

-

-

-

- Elders from different cultures and places, as far apart as Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the Amazon Basin, who want to meet to share Knowledge and wisdom can apply for funds to cover travel and meeting costs.

-

-

-

- Individuals who want to travel to and study with an Elder who has agreed to teach them a certain type of IK can apply for funds to cover travel and a per diem that will support them while they work full-time with the Elder, and can also provide the Elder with an honorarium that supports them as they do this sort of work.

-

You can learn much more about Indigenous Knowledge and the kinds of environmental work IKhana Fund supports from the Story “What Comes Through the Fence,” here.

Why should I support Indigenous Knowledge instead of environmental organizations?

Environmental organizations do important work. We are not claiming to be more important than they are — just different. Indigenous Knowledge provides truly innovative solutions that aren’t otherwise available to communities struggling with ecological and environmental change ranging from soil nutrient depletion to dramatic changes in seasonal rainfall. And IK solutions are themselves adaptable as conditions continue to change, through the continued use of Indigenous Knowledge. Further, IK provides ecological or scientific-type knowledge, but also other kinds of important knowledge as well. It gives humans the tools such as specific song and ritual that they need in order to care for and nurture the Land — the plants, animals, waters, and soils — to give back to them in a reciprocal way — which helps these things be healthier and more resilient again. The Earth has wisdom of its own, knowledge that humans do not know and cannot know by just our own cognitive process alone. Indigenous Knowledge provides access to a wisdom that is strikingly timely and also powerfully timeless.

Environmental organizations do important work. We are not claiming to be more important than they are — just different. Indigenous Knowledge provides truly innovative solutions that aren’t otherwise available to communities struggling with ecological and environmental change ranging from soil nutrient depletion to dramatic changes in seasonal rainfall. And IK solutions are themselves adaptable as conditions continue to change, through the continued use of Indigenous Knowledge. Further, IK provides ecological or scientific-type knowledge, but also other kinds of important knowledge as well. It gives humans the tools such as specific song and ritual that they need in order to care for and nurture the Land — the plants, animals, waters, and soils — to give back to them in a reciprocal way — which helps these things be healthier and more resilient again. The Earth has wisdom of its own, knowledge that humans do not know and cannot know by just our own cognitive process alone. Indigenous Knowledge provides access to a wisdom that is strikingly timely and also powerfully timeless.

Why are you holding organizational meetings before issuing your first Call for Proposals?

It’s going to take serious planning to establish a grant system that operates within Indigenous worldview. The Call for Proposals, review criteria for proposals, and system of reporting results back to the IKhana Fund must permit proposal evaluation within Indigenous worldview so we can fund projects in as fair a way as possible.  We seek community input from Indigenous scholars, teachers, Elders, artists, and others who can help us design criteria that will best serve our community. Informal discussions with colleagues allowed us to determine the feasibility of what we want to do, so we are moving ahead on our plans. We carried out the first organizational meeting in 2022 and issued the report, “Standing Our Ground for the Land: An Indigenous Philanthropy.” Now, with the support of a generous grant from The A Team Foundation, we are carrying out the second phase of that planning process in 2023. If you feel moved to support our work as we continue to develop a new model for funding Indigenous Knowledge research, please contact Shawn Wilson, Ph.D. (Opaskwayak Cree) or Dawn Hill Adams, Ph.D. (Choctaw).

We seek community input from Indigenous scholars, teachers, Elders, artists, and others who can help us design criteria that will best serve our community. Informal discussions with colleagues allowed us to determine the feasibility of what we want to do, so we are moving ahead on our plans. We carried out the first organizational meeting in 2022 and issued the report, “Standing Our Ground for the Land: An Indigenous Philanthropy.” Now, with the support of a generous grant from The A Team Foundation, we are carrying out the second phase of that planning process in 2023. If you feel moved to support our work as we continue to develop a new model for funding Indigenous Knowledge research, please contact Shawn Wilson, Ph.D. (Opaskwayak Cree) or Dawn Hill Adams, Ph.D. (Choctaw).

Click here to return to main IKhana Fund page

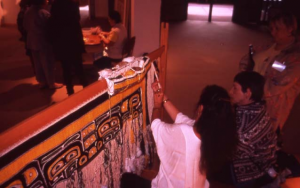

— All photographs on this page are copyright Tapestry Institute. The photograph of the rainbow at the top of the page was taken on the Pine Ridge of northwestern Nebraska. All other photos are from the conference “Stories from the Circle: Science and Native Wisdom”, organized and led by Tapestry Institute in 2002. The weaver shown from behind is the late Tlingit artist Clarissa Rizal, demonstrating Chilkat weaving to an NSF Program Officer. The large piece of glass artwork visible in another image is by Preston Singletary, submitted to the art show held in conjunction with the conference. —