Evaluating stories and images can help people learn to see the paradigms that influence the behaviors and values of their own culture. It also allows people to reflect on the subconscious ways these paradigms might be influencing their own thinking or behavior. I hope the small number of “evaluation exercises” in this work are therefore useful, even though they are obviously quite simple compared to the work professional evaluators carry out.

An Associated Press story in 2009 reported that (AP 2009):

“With the world losing the battle against global warming so far, experts are warning that humans need to follow nature’s example: Adapt or die. That means elevating buildings, making taller and stronger dams and seawalls, rerouting water systems, restricting certain developments, changing farming practices and ultimately moving people, plants and animals out of harm’s way. . . The Thames Barrier has 10 steel gates that protect London from tidal surges but, fearing rising seas from global warming, Britain is investing $500 million to beef up those defense.”

This short paragraph expresses several important paradigms about humans and ecosystems, two of them in direct conflict. Most of the rest of this page engages you in thinking and writing about a series of questions that help you evaluate that one paragraph and its very deeply-rooted paragmatic context.

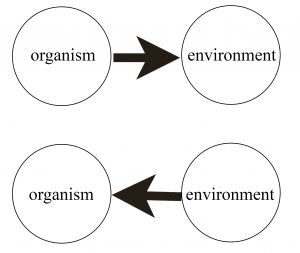

Let’s start by thinking about the classical definition (please note my adjective “classical” there) of the term adaptation: that it is the evolutionary change of an organism in response to its environment so it fits that environment well enough to thrive, and that organisms that fail to do this go extinct. The cited paragraph implies this classical meaning of adaptation most clearly in the phrase “humans need to follow nature’s example: Adapt or die.” So let’s begin there. Look at the two diagrams below and think about which one depicts a picture of an organism changing in response to its environment. If it helps, reframe the sentence as “which one shows the environment causing change in an organism.”

Now look at these specific examples of human adaptation to climate change the article lists: “making taller and stronger dams and seawalls” and beefing up “The Thames Barrier” of “10 steel gates that protect London from tidal surges.” Which of the two diagrams depicts the actions those specific examples describe? Do these phrases describe the environment changing an organism? Or do they describe an organism changing the environment?

Perhaps you see the paradigmatic conflict here, between a classical definition of adaptation and a paradigm that’s about something so different from adaptation that it’s not adaptation at all. If so, notice how deep the roots are on this “not adaptation” paradigm: it’s somehow over-written the classical definition of adaptation without either the reporter, the editor, or (presumably) most of the readers noticing any problem. I’d like to ask you to give this other, more deeply-rooted paradigm a name of some kind to help you think about it. Write down the name you’ve given this paradigm, and explain that name’s origin. As you think about it, where else do you see this same paradigm guiding human behaviors? Can you name a couple of situations in which it seems to have had a “positive” impact? Can you name some situations where its impact seems to have been more “negative”? What outcomes or values do you find you use to decide whether a given outcome or impact of this paradigm on human behavior is positive or negative?

How might resilience ecology’s principle of Robustness-Fragility Trade-Off intersect or interact with the idea that human behaviors such as building taller and stronger seawalls are adaptive? What about the two laws John McPhee observed? Does thinking about either of these understandings of human-nature interaction change the way you think about any of the situations you just described, where the “deeply-rooted not-adaptation paradigm” had a positive or negative impact?

The simple diagrammatic representation of “classical” adaptation on this page (circles and arrow above), that you used to help you analyze the paradigms in the AP paragraph, depicts the understanding of adaptation that the story referenced. But it’s a view of adaptation that’s 50 years out of date. That’s why we had to reach over to pull RFTO and McPhee into the discussion. Now, as you think about the potentially negative impacts of human behaviors driven by this deeply-rooted paradigm you’ve given a name, consider maladaptation and the way our river-stone metaphor of maladaptative traits relates very specifically (as it happens) to seawalls in ecosystems where adaptation is an emergent phenomenon. Take a moment to weave your thoughts and those ideas together.

Does it change how you see this passage (below) from the original paragraph, if you put it in the context of contemporary scientific understandings of adapation and maladaptation?

“With the world losing the battle against global warming so far, experts are warning that humans need to follow nature’s example: Adapt or die. That means . . . making taller and stronger dams and seawalls . . .[and strengthening] The Thames Barrier [that] has 10 steel gates that protect London from tidal surges. . . “?

Some of the behavioral changes the AP article lists are not apparently maladaptive. These include “elevating buildings, . . . rerouting water systems, restricting certain developments, changing farming practices and ultimately moving people, plants and animals out of harm’s way.” It’s possible some of these behaviors could be considered adaptive in the resilience ecology sense of having emerged from the whole complex ecosystem. How might you be able to evaluate whether or not these behaviors are really adaptive in the complex adaptive ecosystems paradigm?

Click here to return to the list of pages at Weaving the Basket.

Click here for list of References.