NOTE: This page will make much more sense if you read the introductory page about Linear and Circular Economies FIRST, and then read this one second.

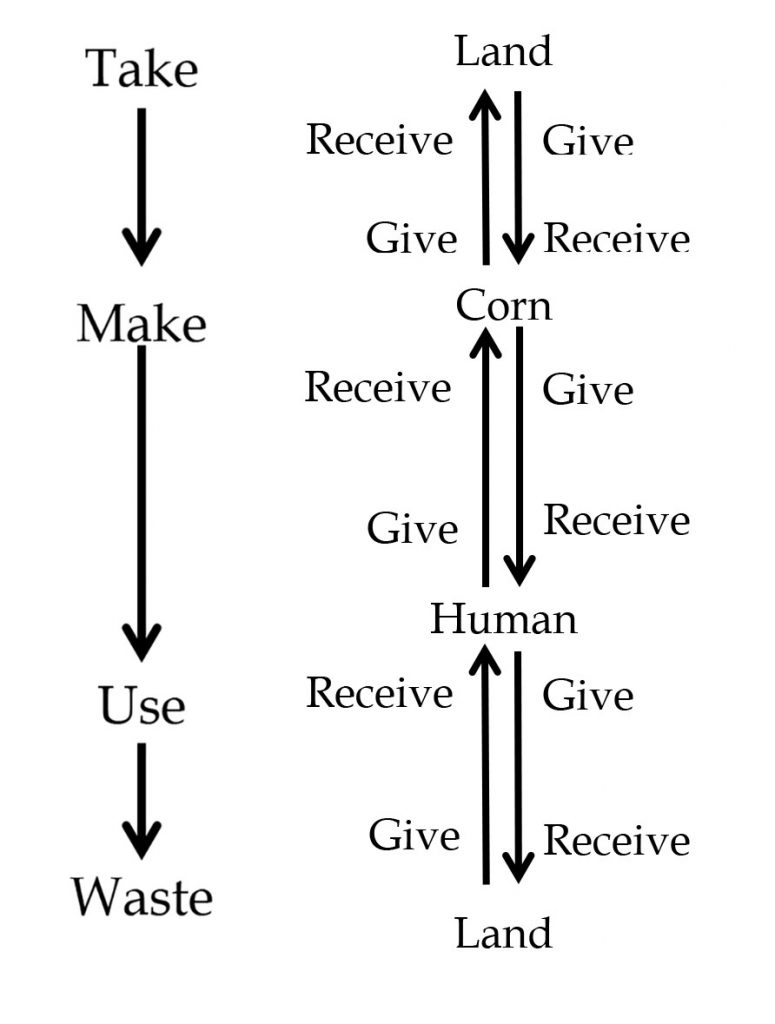

The picture on the right is my redrawn diagram of what a “linear economy” diagram might look like in a system where people and planet are, in fact, intertwined. First, I added nouns representing the subjects and objects engaged in actions (verb things) such as “take” and “use”. Here I went ahead and pegged the ultimate source of the materials “taken” into any economic system by putting the Land at the top of the diagram. And since waste materials ultimately return to the Land via decomposition (even if that takes a long time), I put Land is at the bottom of the redrawn linear economy diagram too.

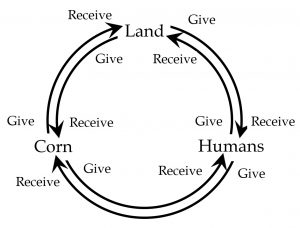

Paying attention to the original “take” and “waste” ends of the diagram changes the diagram in a really important way. The “line” becomes a circle, since the Land is at both the top and. the bottom. So below you can see it redrawn as the circle it actually is. (I suspect this was the original intention of the figure before it got waylaid by the old paradigm.)

So is there even such a thing, then, as an economic system that is actually linear? Think about this a moment. Don’t worry about economic theory; just think about the two ends of the linear economy “take” and “waste.” Is there ever any way those are not actually connected somehow? If waste was loaded into rockets and shot into space, perhaps this could be claimed (though I think most Indigenous people, including myself, would disagree).

So is there even such a thing, then, as an economic system that is actually linear? Think about this a moment. Don’t worry about economic theory; just think about the two ends of the linear economy “take” and “waste.” Is there ever any way those are not actually connected somehow? If waste was loaded into rockets and shot into space, perhaps this could be claimed (though I think most Indigenous people, including myself, would disagree).

It’s also important to notice that although the circular economy diagram in the original illustration is (I think) meant to be a sort of “after” or “destination” view of economies, it still has a linear “take” portion at the top that’s far more pervasive than is apparent until you redraw the diagram. Significantly, that upper “take” portion remains unconnected to any “waste” part of things. The circle never actually closes so even the original circular economies diagram remains linear.

So even though the stated purpose of the UN report whose figures I’ve redrawn is “to redesign a path to progress that respects the intertwined fate of people and planet,” somehow the diagram inadvertently posits the possibility that an economy can exist wholly separate from the planet, and that waste does not return to the planet, and so an economy can exist that is actually linear. No matter whose worldview you’re in, I don’t think this is ontologically possible.

If the stated purpose of the original UN report had been to make a claim that human economies are wholly unconnected to the natural world and can be literally linear, producing waste that does not return to the ecosystem, the diagram would at least illustrate the point the report was trying to make. But it still would not be true or even ontologically possible.

There is no such thing (ontologically speaking) as a human economic system that floats in a sort of vacuum, unconnected to the natural world and with its “waste” somehow evaporating into literal nothingness. So how did it wind up depicted in this diagram?

Let that interesting thought mingle for a moment with the old linear cause-and-effect model of the natural world we’ve seen here and there.

There’s one last thing to point out about my redrawn diagram: I replaced the one-way arrows with two-way arrows, and I altered the verbs involved. That’s because there is no “take” in a real economic system where humans are part of nature. Instead, in the real, complex, natural social-ecosystem world whose functionality is powered by the dynamic and nonlinear richness of its web of relationships, there is “give” and there is “receive.”

Potawatomi scholar Kyle Whyte tells us that environmental scientist Robin Kimmerer, who’s also Potawatomi, calls this set of mutual transactions a “covenant of reciprocity” (Whyte 2018:127). Whyte himself defines reciprocity, in part, as “the moral quality of being accountable for returning what one has been given.” (Whyte 2018b:140). Reciprocity is not a minor point, nor is the way I’ve added it to this diagram. Reciprocity is the core, the central tenet, of the specific Indigenous understandings of deep sustainability that people of Western culture yearn to somehow comprehend.

So. You see why this diagram was worth evaluating and redrawing. What may have seemed like a minor issue of picky semantics turns out to lead directly to the core of things.

Cherokee scholar Jeff Corntassel (2014) points out that in Indigenous worldview, “meaningful environmental sustainability [is] grounded in reciprocity, respect, and resilience,” and sustainability is ultimately “about nurturing and honoring the relationships that promote the health and well-being of communities and individuals.” By “communities and individuals” here, Corntassel refers to all the communities and individuals of entire ecosystems — those that Western culture considers living and also those that Western culture views as inert, physical, or geological. Reciprocity is an essential moral principle because it upholds the health and well-being of everything that exists. Remember that in real complex natural systems, it is relationship that gives rise to everything that ultimately matters. And reciprocity is the foundation of healthy relationship. The “give” and “receive” arrows show the actions of reciprocity. Comparing the original diagram to the redrawn one shows you that being “green” is not about “taking less.” It’s about not “taking.”

Click here to return to the page with the original economy diagrams.

Click here to go to the page with my redrawn circular economy diagram.

Click here to return to the list of pages at Weaving the Basket.

Click here for list of References.