Page 10 of The Mythic Roots of Western Culture’s Alienation from Nature. Adams and Belasco. Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, Volume 1, Number 3. July, 2015. Outline / List of Headings available here.

Lived Expressions of the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth in the External World

One of the primary tenets of the Jungian view of Myth is that because it comes from the collective unconscious, people act out Myths even when they are consciously unaware the stories exist. Myth informs peoples’ assumptions about “what should happen” and what it is “right” to do. So the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth is expressed in the actions of people in Western culture.

1. Lived Expressions of the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth in Desert Ecosystems.

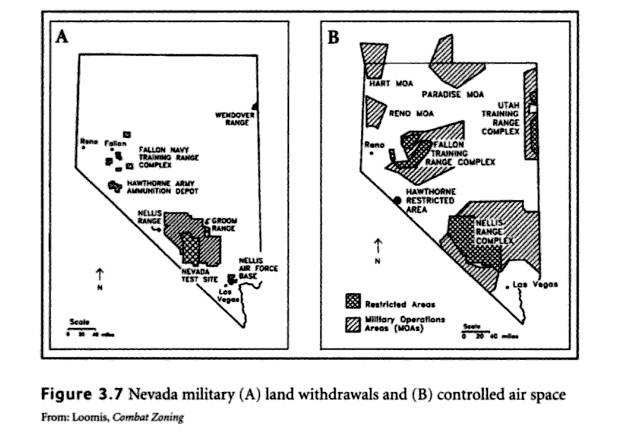

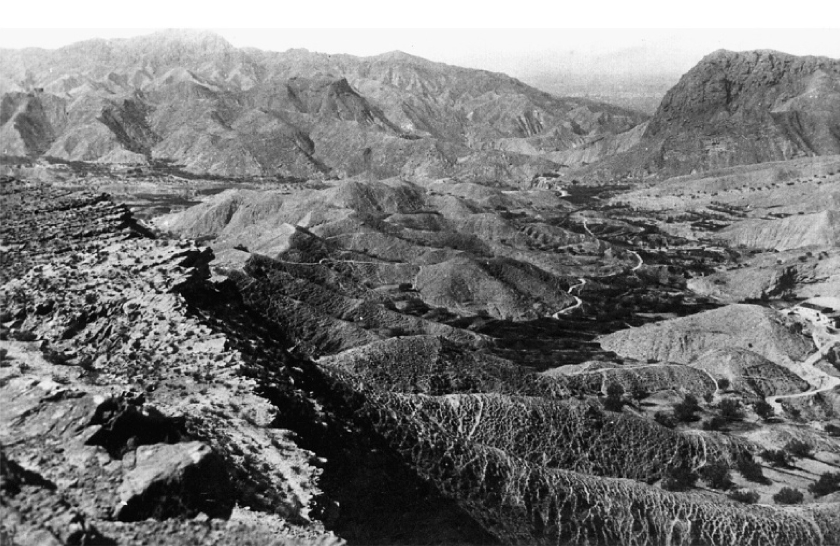

The deserts of what is now the southwestern United States are home to military bombing and gunnery ranges, war games theaters, armament and radioactive waste dumps, and test and development facilities for both conventional and nuclear weapons. These facilities and the controlled airspace above them occupy almost half the land area of the state of Nevada alone, and extend into the deserts of Utah, California, Arizona, and New Mexico (36). Deserts were selected for these purposes at a time when landscapes of many kinds across the U.S. were still largely uninhabited because desert land “. . . wasn’t really much good for anything but gunnery practice – you could bomb it into oblivion and never notice the difference.” (37; italics added by V. Kuletz)

Many people of Western culture see the desert as an inhospitable no-man’s land with no intrinsic merit. They speed through Nevada with their car’s air conditioners on high, hoping not to break down in the heat. Or they outfit their cars for desert travel and intentionally journey off road to heroically test themselves in the same arid landscape. Both sets of behaviors are lived expressions of the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth.

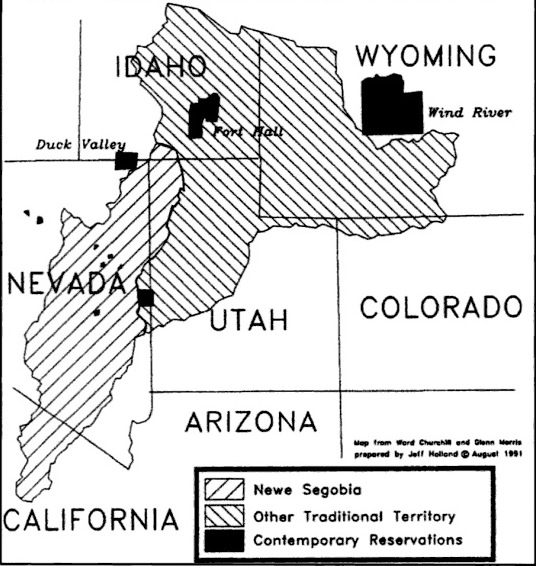

It is fairly easy to see this view of the desert is mythic and cultural rather than actual. Before the deserts of Nevada were turned to military use, they were the ancestral homelands of the Shoshone and Paiute. These people do not see the desert or relate to it through the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth. Barbara Durham, Death Valley Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe writes (38):

“Our desert lands need protection because they are lands that have significant importance to us, the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe, neighboring tribes and the desert communities. Areas such as the Avawatz Mountains, the Panamint Valley, the Coso Range area, Silurian Valley and the Kingston Range all matter to us; their presence is valued for their history, landscape, story telling and connection with our ancestors who lived here and enjoyed them as much as we do today. The plants, animals and people of these areas have survived through countless hostilities and threat of extinction but we always persevered because it is our duty to protect our lands, our homes, our way of life and ties to our aboriginal territories.”

Of course, the difference between Shoshone and Paiute views of desert land and the U.S. military view informed by Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth creates serious cross-cultural conflict (39).

Yet unconscious Mythic views of reality are not hard-wired into individual behavior or social policy. Edward Abbey wrote of the beauty in desert landscapes with reverence, as did John Muir. Even the federal government’s National Park website for Death Valley uses appreciative language to describe the desert environment. Notice the caveat of the highlighted passage, though: that the desert’s beauty and abundance exist “Despite the harshness and severity of the environment” — as opposed to because of the uniqueness of an environment with low humidity and lots of sunlight (40; bold emphasis added by authors).

“Death Valley: The name is forbidding and gloomy. . . Despite the harshness and severity of the environment, more than 1000 kinds of plants live within the park. Those on the valley floor have adapted to a desert life by a variety of means. Some have roots that go down 10 times the height of a person. Some plants have a root system that lies just below the surface but extends out in all directions. Others have leaves and stems that allow very little evaporation and loss of life giving water. . . Death Valley’s great range of elevations and habitats support a variety of wildlife species, including 51 species of native mammals, 307 species of birds, 36 species of reptiles, three species of amphibians, and five species and one subspecies of native fishes. Small mammals are more numerous than large mammals, such as desert bighorn, coyote, bobcat, mountain lion, and mule deer. Mule deer are present in the pinyon/juniper associations of the Grapevine, Cottonwood, and Panamint Mountains.”

Comparing views of the desert that made it an “obvious” choice for testing bombs to views expressed in the Death Valley National Park text show why it’s been a contentious issue for scholars to determine how Western culture really sees nature, and why. Yet notice the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth is still present even in the appreciative Park text, hidden in the apparently simple prepositional phrase “despite the harshness and severity of the environment.” The Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth is often submerged beneath the surface of positive Western views of nature this way, like an alligator with only its eyes visible above the water line.

2. Lived Expressions of the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth in Forest Ecosystems.

Deforestation is typically seen as a natural consequence of ever-increasing human needs for fuel, construction material, and cleared agricultural fields and pastures (41). Yet the pace of deforestation in areas such as New England, where it happened under the observant eye of people like Henry David Thoreau, suggests the process of logging and clearing forests was not solely a matter of increased resource demand. Thoreau noted that when Concord was settled in 1638, the forest was so dense that “according to one estimate, a typical forest area of ten square miles supported as many as five black bears, two to three pumas and an equal number of gray wolves, 200 turkeys, 400 white-tailed deer, and up to 20,000 gray squirrels.” By 1700, more than half a million acres of New England woodlands were gone; by 1800, most of the original old-growth forest was gone and the wooded areas that remained were usually secondary and tertiary growth. So many animals disappeared during this rapid deforestation that Thoreau never mentions seeing a deer in the 20 years of his writings (42).

We’ve already noted that settling Puritans saw New England’s forests as a rampant wilderness needing to be tamed by cutting and clearing, and that clearing such forests was thought of as a battle between individual people and a wilderness that had to be overcome to create a home and new way of life. So it would be easy to see the record of deforestation in New England as an artifact of pioneering — something present in wild lands being colonized, but not in lands already home to the colonizers.

But large-scale deforestation happened throughout Europe and the Middle East. The treeless Scottish highlands of today were once “home to some of the richest forests in Britain, with bear, lynx, elk, wolf and boar thriving beneath a pine-needle-and-broadleaf canopy that stretched over an area of 1.5 million hectares.” Most of Scottish deforestation was caused by human action (43). The same thing happened to forests in Spain, England, and Germany (ref. 41). When timber was needed to build armadas or cathedrals, forests were cleared without hesitation because they were seen as a dangerously wild threat to people and domestic livestock anyway. The Dark Forest frightened more than just Little Red Riding Hood, and the Woodsman was a Hero in more than one story.

Of course, many people in Western culture see forests as beautiful landscapes. Reforestation efforts are restoring wooded habitat to historically cleared lands in places like Scotland and Spain, and legislation is being enacted worldwide to preserve some of the world’s remaining old-growth forests. As we have pointed out, cultural myths arising from a person’s unconscious are not hard-wired.

Yet at the same time, the unconscious and unrecognized Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth speaks clearly even in places we don’t expect it, in the voices of people who probably aren’t aware of its presence there. Robert Frost’s famous poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” says quite clearly that “The woods are lovely, dark and deep.” But Frost also speaks of the snowy woods that attract him so powerfully as belonging to someone rather than being wild, and as a place a person doesn’t normally stop or live but only passes through (45; some lines in bold font for emphasis):

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

That last stanza is filled with Frost’s powerful longing to remain in the woods but his inability to do so. He explains he has obligations that demand he keeps moving. But the paradigms of human-nature relationship encoded in the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth have more to do with his leaving than any obligation elsewhere. Frost and his pony, paused in indecision at the edge of a dark and snowy woods, are shadowed by the looming mythic figures of Sir Gawain and his stallion, draped in misery, hooves ringing hard on frozen stone in the very same dark forest filling with snow. The mythic story that connects them is a path that winds far beyond the landscapes of New or Olde England, either one.

Continue to Next Section: The Oldest Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth on Record

— or —

Return to: Introduction and Outline / List of Headings

References, Notes, and Credits

for

Lived Expressions of the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth in the External World

36. Valerie Kuletz. 1998. The Tainted Desert: Environmental Ruin in the American West. 368 pages. Psychology Press. (Routledge)

37. David Loomis. 1993. Combat Zoning: Military Land-Use Planning In Nevada. University of Nevada Press. 168 pages. Cited in Kuletz, Op Cit., page 66.

38. “Campaign for the California Desert” website. http://californiadesert.org/supporters/quotes/ Accessed June 26, 2015.

39. Valerie Kuletz, Op cit., pages 63-64.

40. Quote is from “Death Valley National Park.” National Park Service website, webpages “Nature” at http://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/nature/index.htm and “Animals” at http://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/nature/animals.htm. Accessed June 24, 2015. See also Edward Abbey. 1977. Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness. Mass Market Paperbacks, 303 pages.

41. María Valbuena-Carabaña, Unai López de Heredia, Pablo Fuentes-Utrilla ,Inés González-Doncel, Luis Gil. 2010. Historical and recent changes in the Spanish forests: A socio-economic process. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 162:492-506. Available online at http://www.academia.edu/716397/Historical_and_recent_changes_in_the_Spanish_forests_A_socio-economic_process. Accessed June 25, 2015.

42. Donald Worster. 1994. Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas, 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press, New York. pages 66-68.

43. Patrick Evans. 2011. “Caledonia Dreaming.” Geographical (The monthly magazine of the Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers), Vol. 83, No. 1.

44. Loch a Chuirn, Scotland. 2005. Photo by Roger McLachlan. From Wikimedia Commons. Available online at Loch_a_Chuirn_-_geograph.org.uk_-_65632.jpg. Accessed June 29, 2015.

45. Robert Frost. 1923. “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” from The Poetry of Robert Frost, Edward Connery Lathem, ed. Available online at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/171621. Accessed July 25, 2015.