Page 13 of The Mythic Roots of Western Culture’s Alienation from Nature. Adams and Belasco. Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, Volume 1, Number 3. July, 2015. Outline / List of Headings available here.

Western Cultural Motifs of Nature in The Epic of Gilgamesh

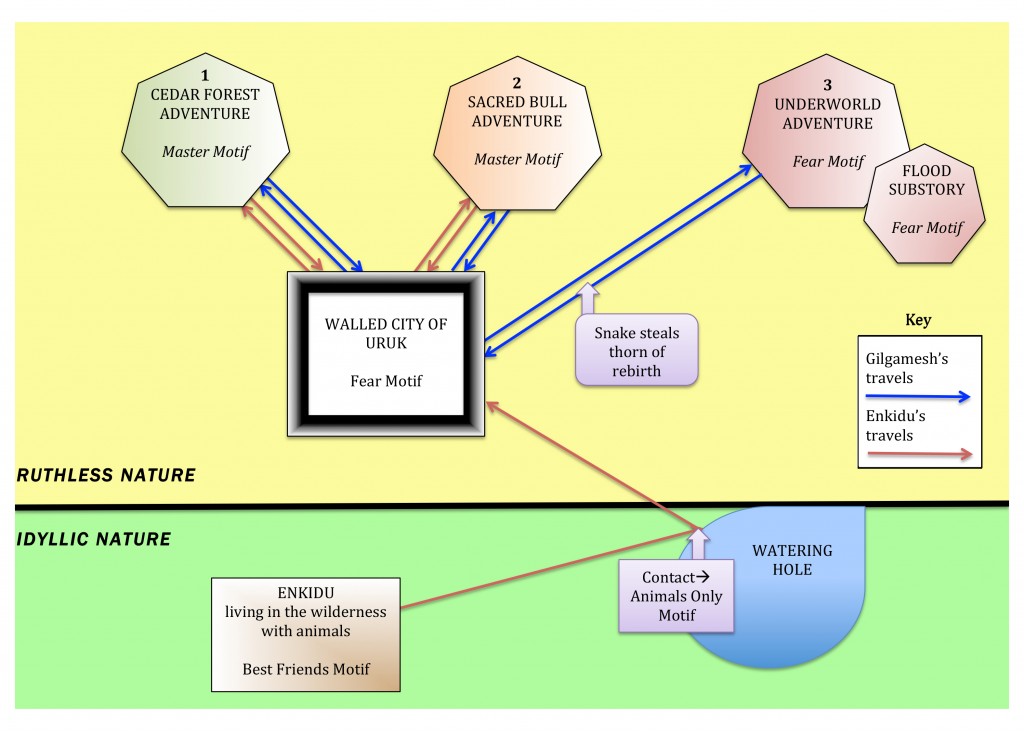

The Epic of Gilgamesh expresses both views of nature and all four major motifs of human-nature relationship we’ve identified in Western culture (Figure 3). Most of the story takes place in the landscape of Ruthless nature. That’s why Uruk has walls, which Gilgamesh built using novel technology that demonstrates a Master motif. But a broader, underlying Fear motif is also present though initially obscured; it’s what motivated building walls around the city to begin with.

Enkidu, by contrast, originates in a place where the view of nature is Idyllic. At first he lives with wild animals in the Best Friends motif, but after contact with people from Uruk he finds himself excluded from nature and therefore in the Animals Only motif; that is, he is no longer a suitable inhabitant of Pristine Wilderness because he is truly human rather than animal. So he leaves Idyllic nature behind and travels to Uruk. In doing this, he crosses into the Ruthless view of nature and enters the landscape of the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth.

Gilgamesh’s first two journeys express the Master motif found in the Ruthless view of nature. Enkidu and Gilgamesh set out defiantly determined to cut down or kill specific entities of nature and do battle with those who would stop them. After the second of these actions, Enkidu is slain as punishment. The Master motif is never expressed in the story again. Instead, Gilgamesh expresses the Fear motif for the first time.

It’s clear that what Gilgamesh fears is death, and that no small part of this is due to the sneaking suspicion that retribution for his acts is going to be levied sooner or later, just as happened to Enkidu. Yet, despite his fears, Gilgamesh sets out on his third and most arduous journey, a search for the antidote to death. To complete his task, he must hear a horrific story that expounds on the Fear motif and tells of lethal retribution delivered via nature to many hundreds of people at once through a terrible flood. Once Gilgamesh has the thorn of rebirth in his hand, he feels temporarily relieved. But when he loses the thorn, he loses any chance of ever feeling safe again and the Fear motif returns. This is where the story ends, with Gilgamesh abruptly going back inside the protecting walls of the fortress Uruk.

Because all the motifs of Western culture’s relationship with nature are present in The Epic of Gilgamesh, we can literally plot contemporary stories on its landscape. Sleeping Beauty and Bambi take place within the parts of the Gilgamesh story that describe Enkidu’s pre-contact and post-contact life in the wilderness, respectively. Stories like Jaws and Twister largely occupy the space of Gilgamesh’s third journey, often starting with fear and vulnerability but ending with a sense of safety brought about by tools, technology, and intellect. In Gilgamesh a snake steals the thorn that was supposed to provide a sense of permanent safety, and few contemporary stories end with such a dramatic loss. Yet at the same time, it’s usually clear the victory in a movie like Jaws or Twister is not permanent; we know a “snake” is coming along someday in the form of a bigger shark or more violent tornado against which the Hero’s tools and technology might be useless.

Historical actions such as deforestation occupy the spaces of Gilgamesh’s first and second journeys: Ruthless nature, Master motif. This is the landscape of Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox, for example, whose stories appeared in northern Michigan around campfires of the very late 1800s. There, between 1875 and 1890, “the loggers not only cleared the pines north of the Saginaw line, they left a layer of slash — the tops and branches of the great logs — sometimes accumulating to a depth of three feet, discarded in the rush to send the timber down the rivers and into the mills.” (61)

Other historic and contemporary actions of people in Western culture can be mapped over the city of Uruk itself. Pioneers in North America recreated Uruk in their forts, walled trading posts, and even “circled wagons.” It was clear to the Native people already living here what those walls were about. As Blackfoot Elder Narcisse Blood observed, “The basis for our relationship with the new-comers was fear. The fear was in the form of the forts, and those big walls they put around themselves to keep them safe from the natives and thus the environment.” (62) Pioneering “civilizing” actions continue today. “Lost whites come to the West to love the environment and they end up paving the damn thing and subdividing it,” Deloria writes in exasperation (63). “This is what you end up with.”

When we see that all four Western cultural motifs of the human-nature relationship were already present in writing 4,000 years ago, in the very place that Western culture itself originated, we realize that Western theology or science cannot have caused contemporary views of nature. They can only manifest the underlying origin common to both. And that underlying origin is deep in the ancient collective cultural unconscious. Because both Idyllic and Ruthless views of nature are present in this earliest Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth, it’s clear the inner turmoil that made Robert Frost yearn to stay in a woods where he was certain he didn’t belong has been present since Western culture began.

Continue to Next Section: Split World, Split Psyche

— or —

Return to: Introduction and Outline / List of Headings

References, Notes, and Credits

for

Western Cultural Motifs of Nature in The Epic of Gilgamesh

61. Charles E. Little. 1995. The Dying of the Trees: The Pandemic in America’s Forests. Penguin Books, New York. pages 111-112. The first Paul Bunyan story to appear in print was written by James MacGillivray and published by the Oscode Press, a northern Michigan newspaper, in August of 1906. Subsequent authors put this and other stories in poem form, then musicians set them to music. The stories are thought to have originated in folk form in the lumber camps of the area.

62. Narcisse Blood interview. Relearning the Land: A Story of Red Crow College. 2015. Multi-Sense Media. A production of Enlivened Learning. A film by Udi Mandel and Kelly Teamey.

63. Vine Deloria, Jr. 1999. Spirit & Reason: The Vine Deloria, Jr., Reader. Edited by Barbara Deloria, Kristin Foehner, and Sam Scinta. Fulcrum Publishing Co., Golden, CO. page 229.