Page 15 of The Mythic Roots of Western Culture’s Alienation from Nature. Adams and Belasco. Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, Volume 1, Number 3. July, 2015. Outline / List of Headings available here.

Humanus and Humana

The bonding of Gilgamesh and Enkidu into a single entity is represented in the story as a sexual union.

“The poem comes just short of stating that the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu is homosexual . . . Even before he meets Enkidu in combat, Gilgamesh dreams of him in an image of great physical tenderness. A boulder representing Enkidu falls from the sky; at first it is too heavy to budge, then it becomes the beloved in his arms, stone turning to warm flesh through the power of the metaphor. Gilgamesh’s mother, interpreting the dream, says that that is indeed how it will be, that the boulder ‘stands for a dear friend, a mighty hero. You will take him in your arms, embrace and caress him the way a man caresses his wife.'” (70)

This language repeats in several different places, clearly spelling out the best friends’ complementarity in a way that’s about gender as well as sexuality.

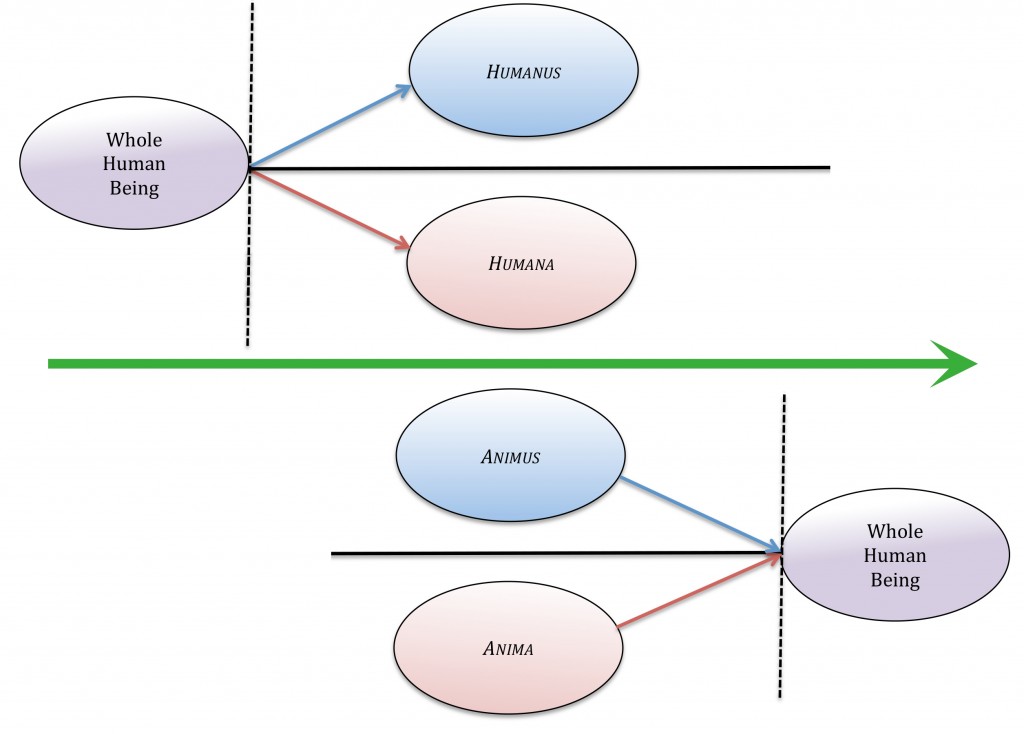

Jung noted the duality of masculine and feminine elements in the human psyche and designated them animus and anima, respectively. He proposed that the process of an individual’s psychological maturation involves reintegrating these dual aspects of innate characteristics. Jung’s student, psychologist and philosopher Erich Neuman explains: “The symbolism of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ is archetypal and therefore transpersonal; in the various cultures concerned, it is erroneously projected upon persons as though they carried its qualities. In reality every individual is a psychological hybrid. . . [I]t is one of the complications of individual psychology that in all cultures the integrity of the personality is violated when it is identified with either the masculine or the feminine side of the symbolic principle of opposites.” (71) Though physically male, Enkidu is represented as a wife or lover because he brings Gilgamesh’s anima to Uruk.

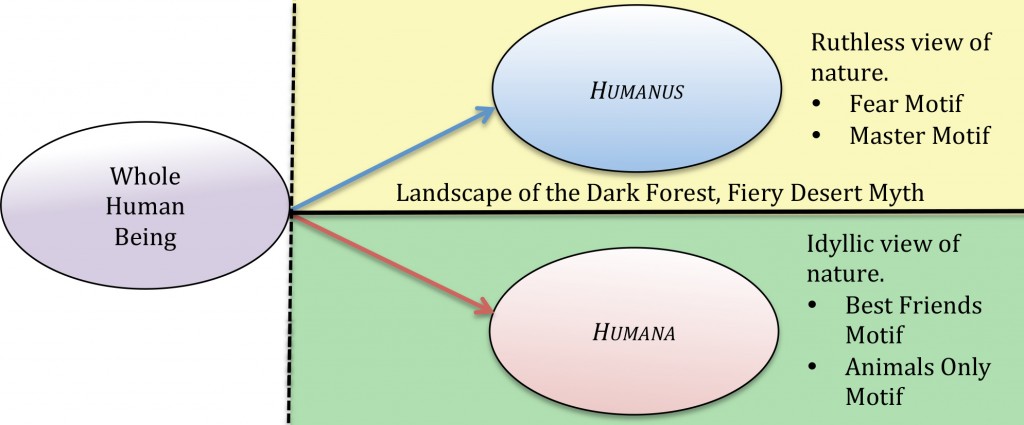

What is more important to our search for understanding Western culture’s view of nature is that the story of Gilgamesh and Enkidu displays a second type of psychic duality, one separate from — but here entangled with — that of gender. It’s the dualistic view of nature as either Ruthless or Idyllic. This duality is in the psyche, or mind; it determines the way people see and relate to nature. The terms “ruthless” and “idyllic” therefore do not refer to nature itself, in an ontological way, but to two states of nature perception. We will use the terms humanus and humana to refer to these dual aspects of psyche that see nature as ruthless or idyllic, respectively (Figure 4). The terms humanus and humana are based on the Latin word for “human being” to highlight the fact that both refer to the human mind and its perception of reality. The use of Latin at all expresses the fact that these terms describe aspects of psyche specific to Western culture, with which the language of Latin is strongly associated.

- The part of a person’s psyche that perceives nature as Ruthless is depicted by the character of Gilgamesh. This aspect of the psyche is the humanus. The humanus‘ relationship to nature is expressed by either the Master or Fear motif.

- The part of a person’s psyche that perceives nature as Idyllic is depicted by the character of Enkidu in his original wilderness environment. This aspect of the psyche is the humana. The humana‘s relationship to nature is expressed by either the Best Friends or Animals Only/Pristine Wilderness motif.

Since the humanus and humana are both present (represented by Gilgamesh and Enkidu) in the earliest written versions of The Epic of Gilgamesh, we know the part of the psyche that perceives nature in Western culture split before 2100 BCE in human populations of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys. Over time the split apparently deepened, as mythic stories of the last 500 years usually express either the perception of humanus (Gawain and the Green Knight, Little Red Riding Hood, Jaws, Twister) or humana (Bambi, Disney’s Sleeping Beauty), but not both in a single image or narrative. All four of the major Western cultural motifs of human-nature relationship (Best Friends, Animals Only/Pristine Wilderness, Fear, Master) are also present in The Epic of Gilgamesh, which is very rare in recent mythic stories and images. The fact that both humanus and humana are present in The Epic of Gilgamesh, and that all four motifs are also present, suggest this particular story was told fairly soon after the historical splitting event took place. That’s undoubtedly what allows The Epic of Gilgamesh to serve as a Rosetta stone for unlocking the mythic information encoded in more recent Western representations of nature and the human-nature relationship.

Humanus and humana are not equally represented in the stories and actions of Western culture. The humanus dominates materials of the last 500 years even more than it dominated The Epic of Gilgamesh. It’s this part of the unconscious psyche that produces and responds to stories and images that perceive nature as Ruthless and the human-nature relationship as in either a Fear or Master motif. It is the unconscious humanus that generates the powerful and frequently told Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth, and it is the humanus that casts nature in the role of Challenger in many Hero’s Journey Myths.

Of course the humana is represented in stories and actions of Western culture as well, as we’ve seen in examples ranging from the movie Bambi to real-life park visitor attempts to pet wild animals. Any material that portrays a Best Friends or Animals Only motif of human-nature relationship comes from the unconscious humana that sees nature as Idyllic. But the voice of the humana is far less common than that of the humanus in the mythic stories and images of Western culture.

An important difference between humanus / humana and Jung’s animus / anima is their relationship to a whole person. Jung saw the animus and anima as present in all people, but initially unbalanced in a way that correlates with a person’s biological gender (e.g., women would naturally have a stronger anima and weaker animus). He saw development and integration of an individual’s naturally “opposite” gender state as a key process in psychological growth (Figure 5). By comparison, the human psyche’s view of nature is initially whole; it has to split apart for a separate humanus and humana to come into existence. The first splitting event occurred in the Tigris and Euphrates valleys before 2100 BCE, and the split has been recreated in each new generation since then by cultural cues such as The Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth.

There is evidence that the unsplit whole human being that is neither humanus nor humana still exists in the Western psyche, though relegated to a deeply unconscious position. One place it’s evident is the Fleeting Moment of Wonder present in many stories that express the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth.

Continue to Next Section: The Fleeting Moment of Wonder

— or —

Return to: Introduction and Outline / List of Headings

References, Notes, and Credits

for

Humanus and Humana

70. Stephen Mitchell translation, from Stephen Mitchell. 2004. Gilgamesh: A New English Version. Free Press, A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. New York, NY. pages 23-24.

71. Erich Neumann. 1954. The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press, Princeton. See http://www2.cnr.edu/home/bmcmanus/anima.html