Page 18 of The Mythic Roots of Western Culture’s Alienation from Nature. Adams and Belasco. Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, Volume 1, Number 3. July, 2015. Outline / List of Headings available here.

Yearning for Wholeness

The nana moma is evident in the oral and written stories of many cultures. Its voice is recognized as one that expresses universal human experience. Joseph Campbell points out, writing about the Hindu Apanishads that were set down about 800 BCE: “Anyone who has had an experience of mystery knows that there is a dimension of the universe that is not that which is available to his senses. There is a pertinent saying in one of the Upanishads: ‘When before the beauty of a sunset or of a mountain you pause and exclaim, ‘Ah,’ you are participating in divinity.’ Such a moment of participation involves a realization of the wonder and sheer beauty of existence. People living in the world of nature experience such moments every day. They live in the recognition of something there that is much greater than the human dimension.” (79)

Clarissa Pinkola Estes speaks the same way about a part of women’s psyche she calls the Wild Woman, which seems to find expression in specific old stories. “When women hear these words, an old, old memory is stirred and brought back to life. The memory is of our absolute, undeniable, and irrevocable kinship with the wild feminine, a relationship which may have become ghostly from neglect, buried by over-domestication, outlawed by the surrounding culture, or no longer understood any more. We may have forgotten her names, we may not answer when she calls ours, but in our bones we know her, we yearn toward her; we know she belongs to us and we to her.” (80) The Wild Woman seems to speak at least in part in the voice of nana moma. It’s suggestive to see how the same passage reads with its words changed only very slightly so it’s about the wild forest instead of story, and the nana moma of both genders rather than only that of women: “When people see a gigantic old tree, an old, old memory is stirred and brought back to life. The memory is of our absolute, undeniable, and irrevocable kinship with the wild, a relationship which may have become ghostly from neglect, buried by over-domestication, outlawed by the surrounding culture, or no longer understood any more. We may have forgotten its names, we may not answer when it calls ours, but in our bones we know it, we yearn toward it; we know it belongs to us and we to it.” (81) For many people, it is reconnection to the nana moma and its relationship with nature that Keen describes in the passage we cited earlier: “Some longing, some missing fulfillment, keeps us searching for a holy grail that is hidden just beyond the mist.” (82)

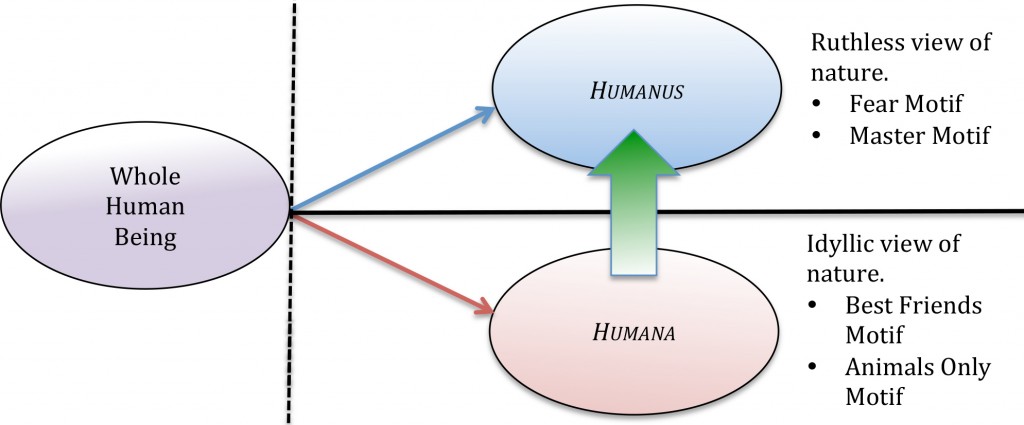

In uniting with Enkidu, Gilgamesh temporarily healed the internal split between humanus and humana within his psyche, which would at first glance seem to reform the whole nana moma. “He saw the Secret, discovered the Hidden,” we are told in the Epic’s opening lines (83). But the solution he found was not sustainable. As we have seen, the only way the two men could unite was for Enkidu to cross into the landscape of Ruthless nature. This required him to change at such a deeply fundamental level that his destruction was then inevitable. Had he lived, he would no longer have brought balancing traits to Gilgamesh, for he had largely become Gilgamesh. It is the newly-developed humanus in Enkidu that throws the hindquarters of the slain bull at Ishtar with a curse. His sudden sense of being split, isolated from the natural world he’s known until now, generates the same “obsessive need to conquer and subjugate” that Theodor Roszak, who popularized the term ecospyschology, sees in Western culture and ascribes to the very same cause (84). Simply importing the humana across the Idyllic-Ruthless boundary does not balance and heal the humanus. After a very brief respite of peace, it destroys the humana instead.

It is this loss — of his own humana — that Gilgamesh mourns when Enkidu dies. We can tell because it is Enkidu’s identity as a part of Idyllic nature that Gilgamesh describes with eloquent words of pain and loss. When he mentions their exploits in the Cedar Forest he does not weep for the lost strength of Enkidu’s right arm or his courage in battle, but instead asks the forest and the trees — parts of nature they destroyed “in our anger” — to join in the mourning as if they were still Best Friends with Enkidu (85):

Just as day began to dawn

Gilgamesh addressed his friend, saying:

“Enkidu, your mother, the gazelle,

and your father, the wild donkey, engendered you,

four wild asses raised you on their milk,

and the herds taught you all the grazing lands.

May the Roads of Enkidu to the Cedar Forest

mourn you

and not fall silent night or day

. . . .

May the pasture lands shriek in mourning as if it were your mother.

May the [unclear text], the cypress, and the cedar which we destroyed in our anger

mourn you.

May the bear, hyena, panther, tiger, water buffalo, jackal,

lion, wild bull, stag, ibex, all the creatures of the plains

mourn you.

. . .

Enkidu, my friend, the swift mule, fleet wild ass of the mountain,

panther of the wilderness,”

It is Enkidu’s death, the death of the yearned-for humana, that drives Gilgamesh to seek a medicine conferring immortality. If he’d wanted it for himself, he should have used it the moment it was in his hands. But he didn’t. Gilgamesh was taking the thorn back to Uruk. When he loses the thorn, he loses the chance of ever restoring life to the part of himself that’s been lost forever: “At that point Gilgamesh sat down, weeping, his tears streaming over the side of his nose.” (86) Within a matter of 11 more lines of text, Gilgamesh is back inside the safe fortress walls of Uruk. And 7 lines after that, the story comes to an abrupt end. There are no more adventures.

The Epic of Gilgamesh ends with the humanus in hopeless isolation, fearing Ruthless nature, mourning the forever-lost humana it believes could have restored wholeness and for which it yearns endlessly.

This is where Western culture has dwelt ever since.

Continue to Next Section: Restoring Wholeness

— or —

Return to: Introduction and Outline / List of Headings

References, Notes, and Credits

for

Yearning for Wholeness

79. Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyer. 1988. The Power of Myth. Doubleday, New York. page 207

80. Clarissa Pinkola Estes. 1992. Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. Ballantine Books, New York. page 5.

81. The relationship between women (and therefore the anima) and the nana moma — which Estes calls the Wild Woman — is significant in Western culture though we cannot address it in this paper. We will pause to make only three observations. First, as Estes says, “It is not so coincidental that wolves and coyotes, bears and wildish women have similar reputations. They all share relate instinctual archetypes, and as such, both are erroneously reputed to be ingracious, wholly and innately dangerous, and ravenous.” She is pointing out that at least sometimes the humanus perceives women the same way it perceives nature. Our second point is that this co-identification of women and nature is the primary premise of a field of academic research called ecofeminism. And our third point is that this conflation of women and nature, with a projection of humanus actions onto the goddess Ishtar, is present in The Epic of Gilgamesh (Tablet VI, when Gilgamesh co-identifies Ishtar’s lover Tammuz with various animals in nature).

82. Sam Keen. 2013. “The Questing Mind: Opening Up to New Possibilities.” Omega. (Omega Institute for Holistic Studies Website) Available online at http://www.eomega.org/article/the-questing-mind. Accessed June 25, 2015.

83. The Epic of Gilgamesh, Op. cit., Tablet I. http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/tab1.htm

84. Theodore Rosak, cited in Rinda West. 2007. Out of the Shadow: Ecospyschology, Story, and Encounters with the Land. University of Virginia Press. page 10

85. The Epic of Gilgamesh, Op. cit., Tablet VIII. http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/tab8.htm

86. The Epic of Gilgamesh, Op. cit., Tablet XI. http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/tab11.htm