Page 2 of The Mythic Roots of Western Culture’s Alienation from Nature. Adams and Belasco. Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, Volume 1, Number 3. July, 2015. Outline / List of Headings available here.

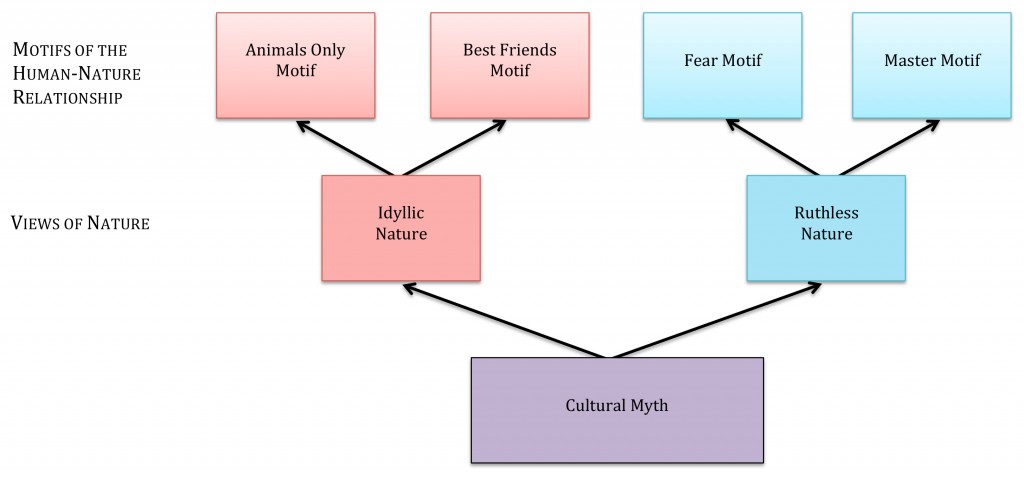

Two Views of Nature and Four Motifs of Human-Nature Relationship in Popular Western Culture

Images and narratives from popular culture provide a place to start our exploration of how and why Western culture sees nature the way it does. Two very different and diametrically opposed views of nature exist. Nature is seen as either an Idyllic environment in which animals live in joyous harmony, or as a Ruthless environment in which animals experience an endless, bloody struggle for basic survival. The first view is generally perceived as naïve and childish, whereas the second view is often considered more adult and realistic. These two views generate four different motifs of human-nature relationship.

In the Idyllic view of nature, there are two motifs of human-nature relationship. In the Animals Only/Pristine Wilderness* motif, humans are excluded from nature for the good of nature itself. When the animals in Bambi warn one another “Man is in the Forest,” it signals impending violence and death. This motif is expressed even more strongly in Felix Salten’s original novel than in the Disney film; a deer who makes friends with humans and insists positive relationship with them is possible pays a terrible price for that view. Crucial aspects of policy development for wilderness areas and parks are often based on the Animals Only/Pristine Wilderness motif and its assumption that human presence is always destructive to nature and must therefore be tightly regulated or even prohibited. The focus of public concern is generally not on the entire natural habitat, however, but on the animals in particular. So, for example, when a massive wildfire burns in a forest where no humans live, news feeds typically feature stories of animals that have been burned, killed, or displaced by the fire rather than on plants, “less cute” animals such as insects, or soil microorganisms. (That’s why we’ve chosen the name “Animals Only,” as prohibitions against plant-human or fungus-human interactions, to name two other possibilities, seem to fall only under a “Pristine Wilderness” point of view.) The “Animals Only” motif of human-nature relationship also generates the viewpoint that humans should not interact with any animals, even as pets. The Animals Only/Pristine Wilderness motif generates conflict between Indigenous peoples and the dominant culture when lands that provide traditional and sacred wild foods are set aside as reserves in which no hunting or fishing are permitted.

In the other motif of human-nature relationship based on the view of nature as Idyllic, humans and animals are Best Friends and have the magical ability to communicate with one another. In Disney films such as Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella, birds and small mammals help their human friend by doing her chores, giving her gifts, and tying ribbons in her hair. Visitors to wilderness areas and national parks sometimes act out the Best Friends motif of human-nature relationship by feeding or trying to pet wild animals such as buffalo and bears, frequently suffering serious injury or death in the process.

The Best Friends motif can also impact cross-cultural communication between Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons because people of the dominant culture sometimes think Native people relate to animals in a “Disney princess” way, communicating with animals via “supernatural” or “extra-natural” means and experiencing magical events as a result.

The alternative view of nature as Ruthless often makes people feel afraid. It’s present in many fairy tales and can be seen in the image of Red Riding Hood walking with great trepidation into the forest in the image to the left. Some anthropologists and biologists see this Fear motif as simply an expression of evolutionary reality: humans instinctively know they are prey and fear predators as a result. In the Fear motif, it’s best for humans to stay out of nature, as it is in the Animals Only motif of the Idyllic view of nature — but this time for the human’s good rather than for the benefit of nature. This type of relationship is seen as a natural consequence of human evolutionary and ecological identity.

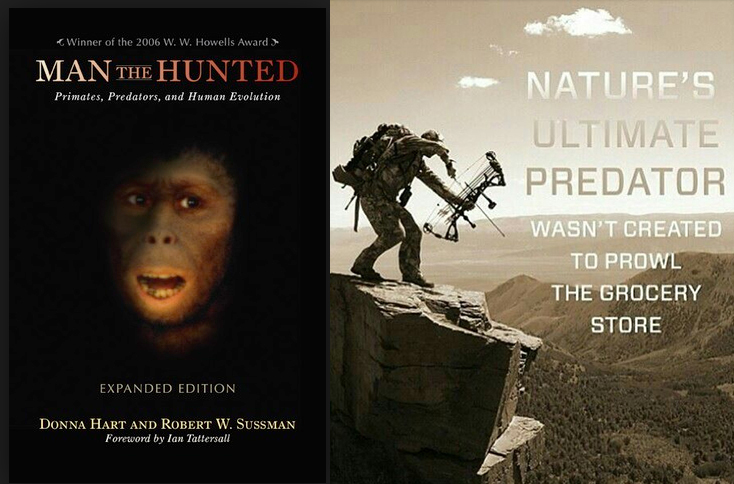

A completely opposite type of human-nature relationship in Ruthless nature view is also said to be an expression of human evolutionary and ecological identity. The Master motif views humans as “top predator,” as popularized by Desmond Morris (13). The Master motif focuses on technology, including tools and tool use, as the key to human-nature relationship, and it extrapolates from actual predators to physical elements of nature such as storms, volcanoes, and drought. So while a movie such as Jaws depicts an actual predator, physical elements of nature also play predatory roles in popular films and stories such as Twister. In that film, a tornado apparently stalks and ambushes the scientist Heroes at the movie’s climax, for example, and a funnel literally growls in several scenes (such as the one below, 14). Movies such as Jaws and Twister usually move characters through a story arc from the Fear motif to the Master motif during the course of the story, with the human Heroes surviving battles with Ruthless nature to win in the end.

(Click the movie poster below to play a scene from Twister. Listen for the tornado’s predatory-animal type of growl at the end of the clip. Please report problems playing the video file.)

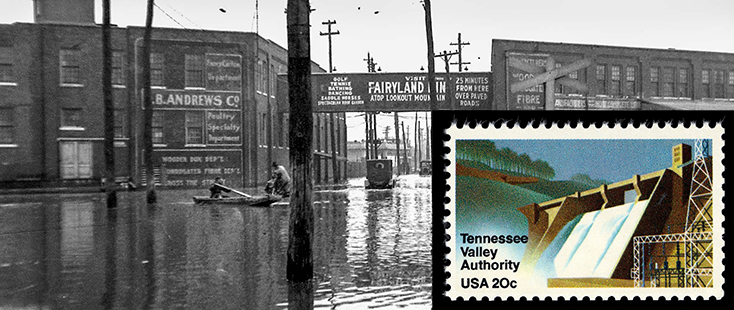

The Fear and Master motifs are particularly prominent in the use of science and technology to protect human lives and livelihood from physical natural hazards. Wildfires that impact humans when the human/nature barrier “breaks down” are frequently approached within this worldview, for instance, with science developing fire retardants that can stop wildland burning. At the other end of the scale, widespread periodic flooding along the rivers of the Tennessee Valley was “mastered” by dams built during the 1930’s Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) project. The Fear motif was present in the public’s dread of recurrent flooding that threatened homes and lives, and the subsequent outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases that often followed. The rivers and mosquitos, plus the diseases the mosquitoes spread, were seen in a Ruthless view of nature. The solution was to switch from a Fear to a Master motif (both still within a view of nature as Ruthless). Mastery of nature was accomplished through the use of human tools and technological know-how to engineer and build dams that controlled floods, restricted mosquito breeding grounds, and even provided hydroelectric power from the waters of the mastered rivers (15).

It’s important to realize there are Western views of nature and of the human-nature relationship that are not represented by these motifs or the views of nature that engender them. Transcendentalism, for instance, was (and is) a complex philosophy that doesn’t fit easily into any of the views we’ve identified in these popular culture motifs. That’s all right because we are not attempting to categorize all of Western culture’s ideas about nature and the human-nature relationship in this paper. Instead, our goal is to use major human-nature relationship motifs of popular culture as a key that will allow us to discover the larger cultural Mythic story about nature that informs these images — and therefore the hearts, minds, and actions of many people in the dominant culture.

The four motifs of human-nature relationship we’ve seen in Western culture’s two main views of nature do not, by themselves, tell us why people of the dominant culture think the world is the way they see it. Because the Idyllic and Ruthless views of nature are mutually exclusive, if we take them at face value the best they can do is point to the existence of two completely separate views of nature in Western culture. That would leave us trying to understand how and why two such diametrically opposed views came to be distributed through various subpopulations of the dominant culture. It makes far more sense to see these dichotomous views of nature as binaries: subsets or parts of a single whole that’s less readily visible. That less-visible whole in this case would be a major cultural myth.

Continue to Next Section: Digging Deeper to Uncover the Underlying Myth

— or —

Return to: Introduction and Outline / List of Headings

References, Notes, and Credits

for

Two Views of Nature and Four Motifs of Human-Nature Relationship

*Note added July 2021: The original designation “Animals Only” motif is hereby broadened to include the term “Pristine Wilderness” as well. This permits the entire range of the view that excludes humans from nature — for nature’s own benefit — to be more readily apparent. Figure 1 does not include “Pristine Wilderness” in its illustration, however. This is an artifact of having added the additional term six years after initial publication of the model presented on this page.

9. Bambi. 1942. Walt Disney Productions. James Algar et al, Directors. Felix Salten, Perce Pearce, Larry Morey et al, Writers. Images on this web page are used under Fair Use as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107.

10. Built for the Kill. 2001. Granada Wild. Andrew Buchanan, Executive Producer. Naomi McClure, Writer. Images on this web page are used under Fair Use as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107.

11. Sleeping Beauty. 1959. Walt Disney Productions. Clyde Geronimi, Director. Erdman Penner, Charles Perrault, et al, Writers. Images on this web page are used under Fair Use as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107.

12. Into the Woods. 2014. Lucamar Productions, Marc Platt Productions, and Walt Disney Pictures. Rob Marshall, Director. James Lapine and Stephen Sondheim, Writers. Images on this web page are used under Fair Use as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107.

13. Desmond Morris. 1969. The Naked Ape. Dell Publishing Company. 205 pages. Seeing humans as primarily “hunted” or “top predators” impacts the ways scientists think about actual human vulnerability and the role of things like fear and aggression in human evolution. So echoes and ramifications of the Ruthless view of nature have deeply influenced evolutionary theory and ecology for the past 40 years and continue to generate controversy and even acrimony in both fields. Morris’s work sits squarely in this context. In some schools of thought, competitive survival of the fittest — “nature red in tooth and claw,” as Tennyson so famously wrote — is seen as crucial for successful continuation of individual genomes, populations, and species. Other schools of thought focus more on cooperation, mutual interactions, and other non-competitive processes, and see events such as extinction as largely random or stochastic rather than caused by lack of fitness. When applied to anthropology, these two schools of thought accord very different weight to processes of aggressive competition or social cooperation, and to the roles of tool use and hand-brain morphology or walking and leg-pelvis morphology, in human evolution. Causation itself, and the assumption of adaptive benefit as a cause for all biological traits, is an underlying philosophical issue in the debate. Possibly the most elegant and cogent statement of the non-adaptive viewpoint is the classic paper “The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme” by Stephen Jay Gould and Richard C. Lewontin, published in 1979 in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B, 205 (1161):581-598. (Available online at http://faculty.washington.edu/lynnhank/GouldLewontin.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2015.) An interesting point to notice is that although one view of nature in these scientific debates is as Ruthless, the other is not of nature as Idyllic. That is to say, a third view of nature is struggling for expression in this field of scholarship. This third view of nature is also apparent in the burgeoning discipline of Resilience Ecology, which has recognized the Master motif present in mainstream ecological science and critiqued its “Command and Control” model of natural resource management. (See, for example, C.S. Holling and G. K. Meffe. 1996. On command-and-control, and the pathology of natural resource management. Conservation Biology 10:328-337.)

14. Twister. 1996. Jan de Bont, Director. Michael Crichton and Anne-Marie Martin, Writers. Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, Amblin Entertainment, and Constant c Productions. Image used under Fair Use as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107.

15. The paragraph about the Tennessee Valley Authority and river flooding was added 6/1/21 to clarify the Fear and Master motifs of human-nature relationship, both of which exist within the Ruthless view of nature. The images beneath that paragraph were added at the same time. Photograph of flooding in Chattanooga, Tennessee is from the TVA website describing the history of Chickamauga Dam. Image of a stamp commemorating and honoring the TVA is from the Smithsonian. Images used under Fair Use as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107.