Page 7 of The Mythic Roots of Western Culture’s Alienation from Nature. Adams and Belasco. Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, Volume 1, Number 3. July, 2015. Outline / List of Headings available here.

Attributes of the Dark Forest in the Hero’s Journey Myth

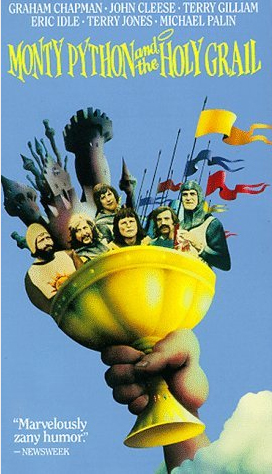

Remember that Campbell describes the Hero’s Journey as leaving “the society that would have protected [him], and [going] into the dark forest, into the world of fire, of original experience.” So the Dark Forest is also an archetypal part of the Hero’s Journey landscape. The attributes of the Dark Forest myth in the Hero’s Journey are so familiar to people of Western culture that they’re parodied in the 1975 movie Monty Python and the Holy Grail (28). Notice the presence and protective significance of the fortress here.

(Click the image to play the video clip. The clip may need time to load. Please report problems playing the video file.)

Looking at that film clip, remember Sam Keen’s quote (see ref. 22): “We are travelers on a journey to an unknown destination. Some longing, some missing fulfillment, keeps us searching for a holy grail that is hidden just beyond the mist.” Of course, Keen did not mention the grail because he had seen this Monty Python movie. Instead, the grail is a significant element of this movie because it is an archetypal “sacred thing” for which a Hero often searches in European Hero’s Journey Myths. The Monty Python movie agrees with Arthurian literature in showing the grail as hidden away in a European castle located in the Dark Forest, but the Crusades in which legendary kings like Richard the Lionheart took part sought the grail in the desert — the same one, more or less, where T. E. Lawrence ventured on a similar adventure a thousand years later. This interesting duality of the grail being hidden away in the castle of a European dark forest or the walled city of a Middle Eastern desert connects those two landscapes and shows they occupy the same archetypal role in the Hero’s Journey Myth almost interchangeably.

You only have to look as far as fairy tales to see expressions of the Dark Forest landscape and understand its attributes, although just a subset of fairy tales express the Hero’s Journey Myth. The fact that some fairy tales are about children who get lost in the Dark Forest, are captured by “ogres, witches or trolls” who live there, and suffer everything from the threat of being eaten to being changed into animals shows very clearly that the Dark Forest Myth is not identical to the Hero’s Journey Myth; instead, they simply overlap sometimes. This is helpful because the Fiery Desert Myth tends to overlap so completely with the Hero’s Journey Myth in stories of contemporary Western culture that they look like aspects of a single myth. For now we will continue exploring examples of the Dark Forest Myth that overlap the Hero’s Journey Myth because it keeps our analysis simpler. But it’s important to remember that the Dark Forest landscape and its metaphorical attributes show up in other kinds of stories as well.

The Old English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (29), thought to have been written in the mid- to late-fourteenth century, tells the story of a Hero’s Journey through the Dark Forest. Sir Gawain of King Arthur’s court goes in search of an adversary called the Green Knight, who he is honor-bound to fight. That search constitutes a Hero’s Journey Myth. Notice the nature and role of the Dark Forest in this passage, the relative challenges posed by human adversaries compared to nature itself, and the role of the castle at the end. We have emphasized some passages with bold font to highlight key points.

Many fells he climbed over in territory strange,

Far distant from his friends like an alien he rides.

At every ford or river where the knight crossed

He found an enemy facing him, unless he was in luck,

And so ugly and fierce that he was forced to give fight.

So many wonders befell him in the hills,

It would be tedious to recount the least part of them.

Sometimes he fights dragons, and wolves as well,

Sometimes with wild men who dwelt among the crags;

Both with bulls and with bears, and at other times boars,

And ogres who chased him across the high fells.

Had he not been valiant and resolute, trusting in God,

He would surely have died or been killed many times.

For fighting troubled him less than the rigorous winter,

When cold clear water fell from the clouds

And froze before it could reach the faded earth.

Half dead with the cold Gawain slept in his armour

More nights than enough among the bare rocks,

Where splashing from the hilltops the freezing stream runs,

And hung over his head in hard icicles.

Thus in danger, hardship and continual pain

This knight rides across the land until Christmas Eve alone. . .

Over a hill in the morning in splendour he rides

Into a dense forest, wondrously wild;

High slopes on each side and woods at their base

Of massive grey oaks, hundreds growing together;

Hazel and hawthorn were densely entangled,

Thickly festooned with coarse shaggy moss,

Where many miserable birds on the bare branches

Wretchedly piped for torment of the cold.

The knight on Gringolet hurries under the trees,

Through many a morass and swamp, a solitary figure, . . .

And therefore sighing he prayed, ‘I beg of you, Lord,

And Mary, who is gentlest mother so dear,

For some lodging where I might devoutly hear mass . . .

Hardly had he crossed himself, that man, three times,

Before he caught sight through the trees of a moated building

Standing over a field, on a mound, surrounded by boughs

Of many a massive tree-trunk enclosing the moat:

The most splendid castle ever owned by a knight,

Set on a meadow, a park all around,

Closely guarded by a spiked palisade

That encircled many trees for more than two miles.

That side of the castle Sir Gawain surveyed

As it shimmered and shone through the fine oaks . . .

The Dark Forest here is wild, dense, tangled, wet, and cold. It is no coincidence that these words describe the landscape through which Sir Galahad struggles in the Monty Python clip you saw earlier. It’s such a miserable landscape that even the birds in the trees suffer. Notice the castle is not in the forest itself but “on a meadow” within a palisaded part of the forest that’s literally a park, its protecting walls a haven that shimmer and shine like a beacon through the trees. The rain, cold, entangling roots, and slavering wolves of the Dark Forest through which Gawain has been riding will not reach a person inside those walls.

Attributes of the Dark Forest that found expression in European epic poetry and fairy tales came to North America with European settlers. In 1646, Puritan leader William Bradford wrote about the colorful autumn foliage in the forests around Cape Cod (30): “What could they see but a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men — and what multitudes there might be of them they knew not. Neither could they, as it were, go up to the top of Pisgah to view from this wilderness a more godly country to feed their hopes; for which way so ever they turned their eyes (save upward to the heavens) they could have little solace or content in respect of any outward objects. For summer being done, all things stand upon them with a weatherbeaten face, and the whole country, full of woods and thickets, represented a wild and savage hue.” British geographer Michael Williams observed that “‘The very size of the forest astonished and frustrated the New World pioneers. . . Because it was impersonal and lonely in its endlessness,’ clearing the forest, in Williams’s view, ‘was likened to a battle or struggle between the individual and the immense obstacle that had to be overcome to create a new life and a new society.'” (31) It is no coincidence that the hero who rescues Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother — by cutting open the wolf who’s eaten them to set them free — is a woodcutter. His ax is wielded as a Heroic weapon against both trees and predators of the mythic Dark Forest.

The basic attributes of the Dark Forest closely parallel those of the Fiery Desert, with a few differences related to specifics of the forest ecosystem:

- The forest is a dangerous environment that ordinary people cannot survive, a place where travel is difficult because of entangling vegetation that isn’t suitable for food or shelter and where exposure to cold, rain, or snow can be lethal. The forest is also full of dangerous predators of many kinds, so an ordinary traveler is likely to be killed or eaten. As a result, the forest tests human beings in a way that forges Heroes of those who survive its passage.

- The forest is not a place where people live, but a landscape through which people journey on a testing “Hero’s Journey” quest.

- The normal landscape of human existence is within the walls of buildings that protect them from the forest. A Hero leaves the walls that normally protect him and other people, goes into the forest to accomplish a Hero’s Journey, and then returns to walls of safety and society that constitute normal human habitation.

Continue to Next Section: The Relationship Between Myth, Stories, Actions, and Culture

— or —

Return to: Introduction and Outline / List of Headings

References, Notes, and Credits

for

Attributes of the Dark Forest in the Hero’s Journey Myth

28. Monty Python and the Holy Grail. 1975. Michael White Productions, National Film Trustee Company, and Python (Monty) Productions. Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones, Directors. Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Eric Idle, Terry Gilliam, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin, Writers.

29. James Winny, Editor and Translator. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. 1992. Broadview Press, Lewiston, NY.

30. Charles E. Little. 1995. The Dying of the Trees: The Pandemic in America’s Forests. Penguin Books, New York. page 126.

31. Ibid, page 125.