Page 9 of The Mythic Roots of Western Culture’s Alienation from Nature. Adams and Belasco. Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, Volume 1, Number 3. July, 2015. Outline / List of Headings available here.

Formal Description of the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth

When attributes of the Dark Forest and the Fiery Desert are combined, we can see a more general Myth about nature and its relationship to people. That larger Myth is about wild nature itself rather than any specific ecosystem. It can overlap with the Hero’s Journey Myth but also frequently overlaps with a different Mythic story in which a Lost Person tries to find the way home again. The Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth may be about landscapes other than forests or deserts, such as oceans and arctic habitats. This Myth exists within and expresses the Ruthless view of nature, and it manifests the Fear motif as a base state of human-nature relationship. The victorious Hero sometimes flips this to a Master motif during the course of the story, as we noted happens in Jaws and Twister.

The Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth: A Hero or Lost Person leaves the normal landscape of walls and buildings that protect humans from wild nature and journeys through a landscape of wilderness. It tests them in a way that develops their personal qualities of heroism, wisdom, and strength because it is an extremely dangerous environment that ordinary people cannot survive: travel is difficult, there is little to no food or shelter, and exposure to predators and the elements can be lethal. A Hero or Lost Person in the wilderness is sometimes lucky enough to find temporary protection, food, and water at an island fortress in the wilderness. After the Hero or Lost Person has overcome the challenges presented, found the way out, or been rescued by searchers, he or she returns to the walls of safety and society that constitute normal human habitation. In the process, the Hero gains a boon that benefits self and others, and the Lost Person finds some version of home and/or learns a valuable lesson.

A few examples of films that strongly express the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth in a variety of habitats include Walkabout (desert), The African Queen (jungle river), The Way Back (taiga, desert, and alpine), and Cast Away (island and ocean). Many 19th and 20th century travel and scientific expedition narratives also express the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth because it deeply influenced the actions of expedition members. An example is The Worst Journey in the World (polar) by Apsley Cherry-Garrard, which tells the story of the ill-fated Scott Expedition to Antarctica.

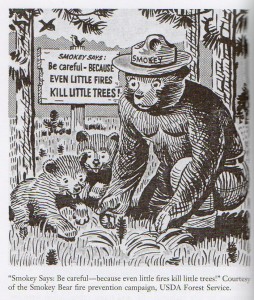

There is no apparent Myth of equal prominence that expresses the Idyllic view of nature in contemporary culture, though later we will explore how this view influences the relationship between people of Western and Indigenous cultures. As we noted earlier, the stories and actions that manifest a Best Friends or Animals Only motif are largely restricted to children’s films and books and to 20th century forestry policies. In forestry materials, the Animals Only motif frequently, if paradoxically, often overlaps with the Best Friends motif. Cartoon images of both Smokey the Bear and Bambi have been used in wildfire safety promotional materials that appeal primarily to children. Interestingly, the Pristine Wilderness motif, which occupies the same mythic space as Animals Only, is the more “adult” version of that human-nature relationship motif. It is generally found in documents and policies that delineate and protect wilderness areas.

There is no apparent Myth of equal prominence that expresses the Idyllic view of nature in contemporary culture, though later we will explore how this view influences the relationship between people of Western and Indigenous cultures. As we noted earlier, the stories and actions that manifest a Best Friends or Animals Only motif are largely restricted to children’s films and books and to 20th century forestry policies. In forestry materials, the Animals Only motif frequently, if paradoxically, often overlaps with the Best Friends motif. Cartoon images of both Smokey the Bear and Bambi have been used in wildfire safety promotional materials that appeal primarily to children. Interestingly, the Pristine Wilderness motif, which occupies the same mythic space as Animals Only, is the more “adult” version of that human-nature relationship motif. It is generally found in documents and policies that delineate and protect wilderness areas.

Continue to Next Section: Lived Expressions of the Dark Forest, Fiery Desert Myth in the External World

— or —

Return to: Introduction and Outline / List of Headings

(No References or Citations for this Section)