NOTE: This paper was originally presented as a keynote address to the Center for Culturally Responsive Evaluation and Assessment meeting in Chicago, Illinois in September, 2014. Although this presentation was developed with that audience in mind, it describes ways of knowing and learning that are — as you will see — universal. The language and syntax of an oral presentation is retained in this text version, and it relies (as did the oral presentation) upon story, image, music, and ritual to illustrate and demonstrate the existence and efficacy of different ways of knowing and learning. It therefore uses images, scenes, and quotes from various media sources, all of which are cited in full. All images in the presentation and on this web page are used under Fair Use as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107. Images on this page may not, therefore, be disseminated.

Assessment as Acculturation:

Procrustes in the Land Between the Mountain and the Sea

Dawn Hill Adams, Ph.D.

Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, Volume 1, Number 2.

May 18, 2015

To cite this article: Adams, Dawn Hill. 2015. Assessment as Acculturation: Procrustes in the Land Between the Mountain and the Sea. Tapestry Institute Occasional Papers, 1(2). https://tapestryinstitute.org/publications/occasional-papers/assessment-as-acculturation-vol-1-no-2-may-2015 *

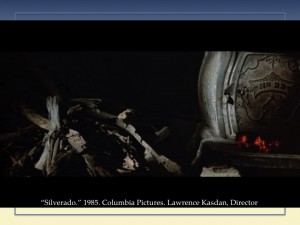

Let us begin our journey together today with one of Western culture’s* favorite stories, as it was told in 1985: the really Western – as in “it has horses in it” Western movie — “Silverado.” (1) I will tell you right now, by the way, you’re going to see a lot of horses in this presentation. Learning always employs a vehicle. Mine happens to be alive and have four legs. You might actually start to wonder after a while, when you see the story return in other places, if I am in fact beating a dead you-know-what with this one movie. And maybe I am and don’t know it. But what I’m hoping to do is build up enough layers of complexity in your mind that a new understanding about the reality of Story will emerge. N. Scott Momaday (2) has said in “The Way to Rainy Mountain” that the most deeply mythic stories are about epic journeys “made with the whole memory, that experience of the mind which is legendary as well as historical, personal as well as cultural.” So let us begin with a short video clip that summarizes the movie’s opening scenes and then reveals its truly mythic nature.

(Please click the image below to see the video clip.)

What we see in the last frame of the clip is “The Box.”

Where we are going today in this presentation is that larger, wilder, and more beautiful landscape of OUTSIDE The Box.

What is “The Box” in the context of this meeting? In education, at least one of the things in “The Box” is: the ways that people learn and know about the natural world, including themselves and other people. Whether we’re talking about valid systems of epistemology or pedagogy, in The Box the information acquired must be testable.

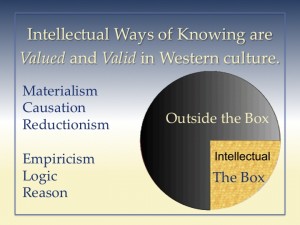

Ways of Knowing and Worldview

Knowledge is only testable within a very specific worldview in which (a) everything real is material, (b) events and actions are produced by causes, and (c) complex phenomena are nothing more than the sum of smaller component parts to which they can be reduced. These aspects of worldview are referred to in philosophy of science as materialism, causation, and reductionism. Materialism posits that only material things are real; causation that things do not arise spontaneously but can be traced back to proximate and distal causes; and reductionism that complex phenomena are reducible to simpler components. Materialism, causation, and reductionism are key components of Western cultural worldview.

Worldview is foundational to culture. It is the way people perceive the nature of Reality and the ways they can and should interact with it. Worldview is such a deeply held set of assumptions about Reality that it usually feels like Reality itself, rather than a set of concepts or philosophies. So people are often unaware that their worldview is conceptual rather than Real.

Knowledge doesn’t have to be testable to be considered true in Indigenous worldview because the Western philosophies of materialism, causation, and reductionism don’t define Reality outside of Western worldview. Interestingly, over the last hundred years, several mathematical and highly theoretical branches of Western physics, chemistry, and biology have re-discovered the existence of natural phenomena such as self-organization and emergence that cannot be explained in terms of simple causation and/or reductionism. Fields such as complexity theory, quantum theory, probability theory, non-deterministic probability theory, and stochastic process research explore examples of, and document the complex mathematics that describe processes such as co-arising, emergence from complexity, and acausal (stochastic) processes. Complexity theory and resilience ecology are examples of two fields of scientific research that explore the non-reducible nature of a number of significant natural processes and phenomena. Unfortunately, this work is not widely known or well-understood outside the home disciplines for these fields, so such ideas have not changed Western worldview in general. It remains largely materialistic, causal, and reductionist. The important thing to understand about these distinctions is that within a worldview that doesn’t define Reality as materialistic, causal, or reductionist, the truth of knowledge cannot always be determined by a predictive test. If prediction is not always possible in Real situations, then testability collapses as a sole means of evaluating truth. This opens the door to many possible ways that people can acquire information from the natural world.

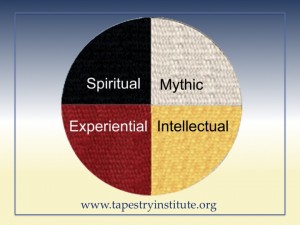

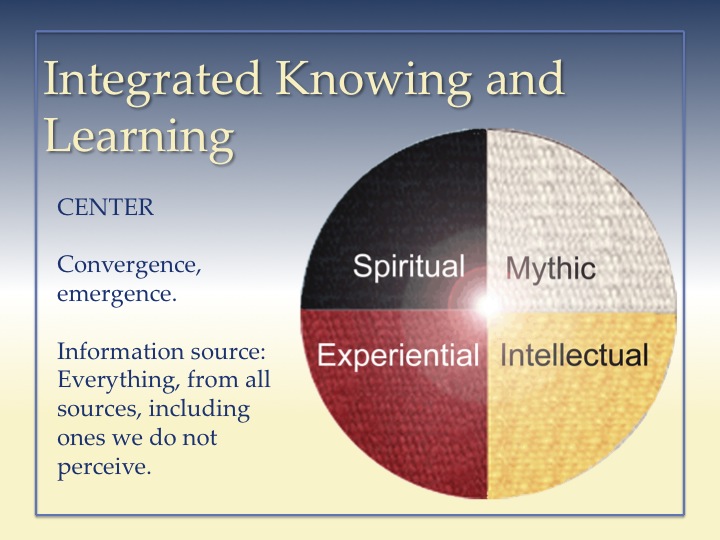

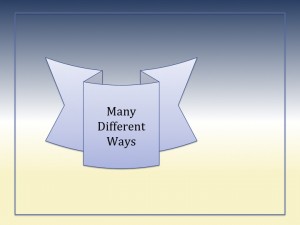

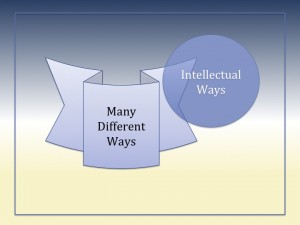

This is a model of the different ways of knowing and learning that we use in our non-profit, Tapestry Institute. The model is based on the Sacred Circle common to many Indigenous North American cultures. The Circle maps multiple and complex layers of reality and has great explanatory power. Because it’s a North American construct, the Circle relates sun and land in a northern hemisphere pattern: the sun enters at the east, then moves in an arc across the southern sky to the west, then back around through north to the east again. Each quadrant of the Circle has a directional aspect that connects it metaphysically – not just metaphorically — to natural events and processes. The colors you see are part of that. It is important to understand this is not “the” Sacred Circle, as there is great variation in form and meaning among the tribes that use it. However, this version is one that’s commonly used in pan-tribal situations. You will see that we have correlated each of the directions with a way that people know and learn. That doesn’t mean we see these ways of knowing as sharply delineated or compartmentalized. The model simply allows us to think about these different ways of knowing a little more analytically. Analysis, by the way, is an “Intellectual” way of knowing.

This is a model of the different ways of knowing and learning that we use in our non-profit, Tapestry Institute. The model is based on the Sacred Circle common to many Indigenous North American cultures. The Circle maps multiple and complex layers of reality and has great explanatory power. Because it’s a North American construct, the Circle relates sun and land in a northern hemisphere pattern: the sun enters at the east, then moves in an arc across the southern sky to the west, then back around through north to the east again. Each quadrant of the Circle has a directional aspect that connects it metaphysically – not just metaphorically — to natural events and processes. The colors you see are part of that. It is important to understand this is not “the” Sacred Circle, as there is great variation in form and meaning among the tribes that use it. However, this version is one that’s commonly used in pan-tribal situations. You will see that we have correlated each of the directions with a way that people know and learn. That doesn’t mean we see these ways of knowing as sharply delineated or compartmentalized. The model simply allows us to think about these different ways of knowing a little more analytically. Analysis, by the way, is an “Intellectual” way of knowing.

Intellectual Ways of Knowing and Learning.

Intellectual Ways of Knowing and Learning.

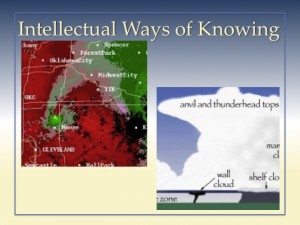

Intellectual ways of knowing and learning are based in rational and logical thought processes. Epistemically, these ways of knowing are testable. Pedagogically, they are testable. Many assessment methods are based on that testability, which is itself a function of the predictable nature of a reality defined by materialism, causation, and reductionism. The information source for Intellectual knowledge lies in either the observable material world (in the sciences) or in highly-developed abstract reasoning (as in philosphy and higher mathematics). If you want to teach someone about tornadoes using Intellectual learning, you explain Doppler radar and what  the different colors on the image (above, right) mean – they show whether the wind is traveling towards the radar receiver or away from it – and then you explain that where winds going in the opposite direction are very close to one another in this shape, it’s because there’s a spinning funnel there – a tornado. Or you can teach people how to identify different kinds of clouds and to know which can produce a tornado, and where they’re most likely to do so. All of this information is testable (3). Academically, as well as more universally, Intellectual Ways of Knowing and Learning constitute “the Box” in Western education. All the other ways of Learning and Knowing are OUTSIDE the Box. And that’s where we’re going, remember: Outside the Box.

the different colors on the image (above, right) mean – they show whether the wind is traveling towards the radar receiver or away from it – and then you explain that where winds going in the opposite direction are very close to one another in this shape, it’s because there’s a spinning funnel there – a tornado. Or you can teach people how to identify different kinds of clouds and to know which can produce a tornado, and where they’re most likely to do so. All of this information is testable (3). Academically, as well as more universally, Intellectual Ways of Knowing and Learning constitute “the Box” in Western education. All the other ways of Learning and Knowing are OUTSIDE the Box. And that’s where we’re going, remember: Outside the Box.

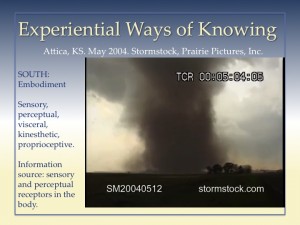

Experiential Ways of Knowing and Learning.

Moving sunwise around the Circle, the next type of Knowing we encounter is Experiential. This type of knowledge is based on information acquired through our sensory and perceptual systems. Earlier I showed you two ways that people can learn Intellectually about Tornadoes. Experiential learning about tornadoes is something I really can’t arrange, which is probably a good thing. But here’s a close approximation. I have stripped the sound off the clip below so it doesn’t trigger PTSD in those of you who may have experienced a severe storm, but I suggest you not watch it anyway if that’s the case. You already have Experiential knowledge of tornadoes if so, and don’t need this video to tell you anything new. It’s important you know that no one was in the structure you’ll see.

(Please click the image below to see the video clip.)

I suspect if I was to hit you with a pop quiz right now and ask you what you just learned, watching that video, we’d hear a lot of gears grinding in the search for words. Emeritus Professor Michael Trimble, Professor of Behavioral Neurology at the University College London explains why in “The Science of Opera,” a 2013 production of The Royal Opera House in conjunction with the Arts Council of England and University College London. In this program, British television personality Alan Davies is presented with a powerful piece of music and then asked to describe it. He is only able to do so by gesturing to his own body. Trimble’s response is:

“I think Alan’s observations of his own body’s responses are very interesting because what he describes is the feeling that begins here [he indicates his midsection], and this is what you call a ‘gut feeling.’ And the main outflow to the guts, as we’ve seen from these slides, is the parasympathetic nervous system, and the sympathetic nervous system…So ‘gut feelings’ are very, very primitive feelings that come from the gut into that limbic system area of the brain. And what is of course quite interesting is that when you get so many gut feelings, that is when you will stop being able to speak. So the emotional arousal, particularly when it comes to tears, although necessarily also laughter, but tears: you can’t speak. So again that’s a good reason why I believe from an evolutionary perspective, these emotional responses to these events predated our ability to use our language.” (5)

By the way, a beautiful image of the Autonomic Nervous System that Trumble mentions, which has Sympathetic and Parasympathetic components (and which you probably remember at least a little from high school biology) is visible online at this University of Tokyo webtext site. The important thing about the Autonomic Nervous System is that it literally connects the basal and deep portions of the brain with the body’s viscera. And that it therefore connects the body, the brain, and emotions into a single functional system.

Spiritual and Mythic Ways of Knowing and Learning.

Moving sunwise, we reach Spiritual Ways of Knowing and Learning. A lot of people think Spiritual Ways of Knowing are about the information transmitted through sacred texts of the world’s major religious traditions. But it refers more to immediate personal experience than to the secondary experience of reading about someone else’s personal experience in a book. Spiritual knowing is a deep understanding that sometimes comes to people in the presence of something that fills them with feelings of wonder, awe, and fear, particularly if that event embodies strong paradox. A common event of this type is childbirth. When the baby’s warm, wet body is first placed in their arms, a parent tends to plunge immediately into goosefleshed wonder at the mystery of life, and then whiplash with real pain to the realization of what it would mean if this child were to die. Birth and death, 10 seconds, deep understanding, typical response: “Oh my God.” There’s even strong paradox in the tornado example we’ve been using. If not for cumulonimbus clouds and the large-scale weather patterns that produce them, there would not be tornadoes. There would also be no rain. Most of the North American interior would be a desert.

I can’t easily create a situation in which you can experience Spiritual Knowing for yourself. Churches, synagogues, and mosques try and often succeed, using music, art, poetic liturgy, ritual, and even specially designed architectural space. Please notice these are all types of ART. Ritual combines Spiritual Ways of Knowing with Mythic Ways of Knowing — including story, art, poetry, music, drama, and/or dance. Ritual creates a doorway through which humans can enter sacred space. Contemporary sandpainter Joe Ben Jr., for example, has said (6), “It’s the medicine men who are the true artists. They must question and interpret. They must journey back within themselves. Artists are just doing what medicine men do.”

So this brings us to Mythic Ways of Knowing. Insight, Inspiration, and Dream are processes through which artists produce paintings or poems. The works of art then transmit information or knowing to those who engage with them. Notice that Mythic Ways of Knowing include the processes at both ends of the sequence of information transmission: through the artist into the piece of art, and through the art to the viewer, listener, or participant.

Mythic Ways of Knowing and Learning: The Archeologist and the Cave Lions

There is good evidence that late Paleolithic European cave art was produced as ritual, not decoration. As ritual, it was intended to engage humans in relationship with the an Outside that was far bigger, wilder, and more powerful than anything most of us have ever experienced. Chauvet Cave in Southern France was sealed from the outside world after Paleolithic times by a rockslide until 1994. The paintings inside, most dating back over 30,000 years, were filmed during one of the few times that scientists were allowed into the cave’s fragile ecosystem to record and study its treasures. This clip from Werner Herzog’s 2010 film “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” (7) illustrates a key archeological theory about the use of animation in these ancient images. The significance of multiple legs and horns on some of the animals, and the consequences of the wall shapes chosen for the paintings and of firelight on the appearance of such images are based on the work of archeologist Marc Azéma and his research partner, artist Florent Rivère (8).

(Please click the image below to see the video clip. This one takes a moment to load.)

In the same film, Herzog interviews archeologist Julien Monney, who is mapping the cave with lasers, about his work. But the interview changes almost immediately to one in which Monney speaks eloquently of the information that is still transferred by this art. In this case, the understanding he received was specifically from images of lions on the cave walls. Monney says: “We are working to create a new understanding of the cave through that precision, through the scientific methods. But that’s not, I think, the main goal. The main goal is to create a story about what could have happened in that cave during the past.” Herzog compares this information to a phone directory that does not tell you if those people dream or if they cry at night. Monney says, “We will never know because the past is definitely lost. We will never reconstruct the past. We can only create a representation of what exists now. You are a human being. I am a human being. And here, when you come to the cave, of course there are some things… I have my own background… The first time I entered to Chauvet cave there was a chance to get in during five days. And it was so powerful that every night I was dreaming of lions. And every day was a same shock for me. It was an emotional shock. I mean, I am a scientist. But a human too. And, after 5 days, I decided not to go back in the cave, because I needed time just to relax and take time to … absorb it.” Herzog clarifies: “You dreamt not of the paintings of lions, but of real lions.” Monney: “Of course. Of course. Definitely. Yeah.” Herzog: “And were you afraid in your dreams?” Monney: “I was not afraid, no. No, no. I was not afraid. ‘Twas more, um, a feeling more of powerful things and deep things. A way to understand things which is not a direct way.”

Music and Musical Theater as a Mythic Ways of Knowing.

Music is often part of religious ritual because it carries even more emotional punch than visual art. Trimble, the behavioral neurologist cited earlier (9), explains that: “I’m very very interested in what happens in the brain and neurology when people are moved to artistic experiences. And I’ve carried out a number of studies over the years looking at the emotional responses. I’m very interested in the different responses to the arts, and crying is important because if you ask an audience such as this ‘How many of you have ever cried to a piece of music?’ you will find 90% of people will admit that. If you then ask how many cried in front of a beautiful painting, how many have cried in front of a beautiful statue or a beautiful building, you’re down to 5 or 10%. In between, you have poetry: people who respond to either reading or listening to poetry. About 60% of people will say they’ve cried. But crying to music is very, very special.”

Western culture generally does not trust emotion. It’s subjective. Intellectual knowing is supposed to be devoid of emotion: purely “objective.” Objectivity is quite literally seen as safer. So, intriguingly, Western culture often uses Story to generate emotions that tell us how dangerous emotion is – and therefore how untrustworthy story is, as a way of knowing. Here’s a clip edited from the ballet sequence of Rogers and Hammerstein’s 1955 film “Oklahoma!” (10) that illustrates this use of art (in this case music, dance, and story) to convey information about the untrustworthiness of emotion. At first you see dancers representing the movie’s Hero, Curly, and his girl Laurie. Then it cuts to the very dangerous Bad Guy Jud, who is driven by dark passions such as lust, hatred, and violence. Notice the physical relationship between Jud and his negative emotions, and the natural world. His posture and movements both literally parallel the threatening and dangerous tornado in the background.

(Please click the image below to see the video clip.)

Integrated Ways of Knowing and Learning.

Integrated Ways of Knowing and Learning.

This brings us to the last way of Knowing and Learning of our Sacred Circle model: Integrated. It turns out that Integrated Ways of Knowing are modeled very well in the real world of human cognition, emotion, embodiment, and sensation — because, of course, all these ways of Knowing and Learning are integrated in practice. You may have noticed how many times, speaking of one of them, I have veered into others to explain. So I am not arguing that Intellectual knowing is invalid or should not be used. I am arguing that ALL the ways of learning and knowing should be valued, used — and integrated. Let me show you what I mean by saying that knowing and learning really are integrated.

A Neurological Model for Integrated Knowing.

A Neurological Model for Integrated Knowing.

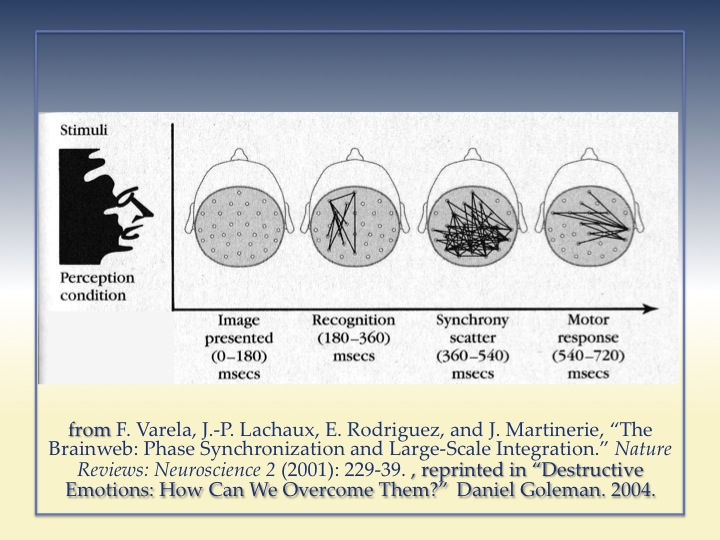

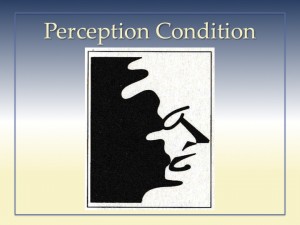

The late Francisco Varela was Fondation de France Professor of Cognitive Science and Epistemology at Ecole Polytecnique; Director of Research at CNRS, Paris; and head of the Neurodynamics Unit at the Salpetrière Hospital, Paris. In one of his most famous studies, he used the image you see to the right. Take a look at it, wait a while, and you will recognize it. Then scroll down past the “spoiler space” I’ve inserted to find out why the image is so meaningful.

You were probably able to perceive a face in the picture after a while: a woman’s face looking to our right, with a fairly sharp nose and her forehead, cheeks, and chin bathed in bright light. Because people are able to perceive the face after studying it for a while, Varela said this kind of image created a “perception condition” in the brain. And what he did was figure out the steps of what happened in your brain, just then, as you recognized that the black and white shapes made a face.

To do this, Varela gave people this and other images and told them to look at it, then push a button when they realized what it was. While subjects were looking at and trying to make sense of these images, EEG electrodes were measuring what happened in their brains. You can see the pattern of activity in the drawings of the image below, which show four stages: the moment the person first sees the image, the period of time during which the person is starting to recognize what the image is a picture of, the instant called “synchrony” when the person goes “Aha!” and understands what they are seeing, and the moment when they move their finger (motor response) to push the button that signals they now know what it is a picture of. At the moment called “synchrony” you see what Varela calls a “scatter” pattern, which refers to the fact that suddenly neurons all over the brain fire at once. This is the instant of “aha” that you felt when you suddenly saw the face. To give you an idea of how rapidly this whole set of processes happens, msec here (in the image above) is milliseconds – one- one/thousandths of a second. Until this study (in Nature Reviews: Neuroscience in 2001), people thought the recognition process was linear, or that it happened in one part of the brain.

Here are the words Varela himself used to explain what happens (11):

“When we perform a cognitive act – for example, we have a visual perception – the perception is not the simple fact of an image in the retina. There are many, many sites in the brain that come active. The big problem… is how these many, many active parts become coherent to form a unity. When I see you, the rest of my experience – my posture, my emotional tone – is all a unit. It is not dispersed, with perception here and movement there. . . How does that happen? Imagine that each one of the sites in the brain is like a musical note. It has a tone. Why a tone? Empirically, there is an oscillation. [Notice the term “empirically.” He means the oscillation is actual rather than metaphoric.] The neurons in the brain oscillate all over the place . . . different places in the brain oscillate, and these become harmonized. When you have a wave here and another there, from different parts of the brain, several become synchronized, so they oscillate together. When the brain sets into a pattern – to have a perception, or to make a movement – the phase of these oscillations becomes harmonized, what we call phase-locked. The waves oscillate together in synchrony. . . . Many patterns of oscillation in the brain spontaneously select each other to create melody, that is, the moment of experience. . . . So again, to understand the large-scale integration of the whole brain, the basic mechanism is the transitory formation of synchronous groups of neurons that are distributed widely. This was a beautiful discovery that gives us an account of how a moment of experience can arise.”

So now you see what happened as you, yourself, went through the recognition process. When you first saw the image, nothing happened. Then there was a moment of starting to see something, when you realized those were glasses or an eye and brow, or maybe you saw the nose shape first. And then BAM – all over the brain – and this is very important – in places all over the brain that are NOT directly connected, groups of neurons began to oscillate in synchrony. And THAT is the moment that you realized: “OH! It’s a woman’s face!” The term for this is “integrated cognition” because all kinds of things are apparently brought into play, from places all over the brain, for that aha moment to develop.

The same process of integrated cognition is being discovered to underlie many of the basic cognitive processes that matter to educators. One prestigious study by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, documented in an MIT publication, should especially interest you (12). In it, researchers gave subjects pairs of words that were either related – table-chair – or unrelated – apple-money. Then they asked them to respond by pressing a button the moment they were able to recognize that the words were related. Sound familiar? Of course, this is a basic element of many standardized tests. It turned out that such word-pair recognition tasks depend on the preceding semantic context, engaging what the authors called a lexical integration process that is “concerned with entering the spoken or written word into a higher-order meaning representation of the entire discourse.” It’s integrated, in other words, rather than linear — just as is the process Varela described.

It turns out that emotion is integrated into the cognitive process as well. As just one example of the data on this, here’s a passage from a 2002 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (13): “Task-related neural activity in bilateral PreFrontalCortex showed . . . an Emotion – Stimulus crossover interaction . . . with activity predicting task performance. This highly specific result indicates that emotion and higher cognition can be truly integrated, i.e., at some point of processing, functional specialization is lost, and emotion and cognition conjointly and equally contribute to the control of thought and behavior.”

So an important reason that ALL the ways of learning and knowing should be valued, used and integrated is that such integration actually mirrors the integration processes of cognition that take place in our brains.

Models of Integration Between Different Academic Disciplines and Different Cultural Worldviews.

Alas, the academic disciplines that use different ways of knowing and learning are not always very integrated. In fact, they often don’t get along. Humanities scholarship courts objectively and uses logic to analyze the facts of art, philosophy, theology, and literature. But many humanities scholars still feel attacked by science. In 1959, philosopher C. P. Snow recognized and articulated this inherent, ways-of-knowing difference between the sciences and humanities by referring to them as “Two Cultures” (14). In 1966, physicist and theologian Ian Barbour applied Snow’s model to a more specific pair of disciplines — religion and science — in his seminal book Issues in Science and Religion (15). He proposed four basic kinds of relationship between the two: Conflict, Independence, Dialogue, and Integration. Although Barbour’s model specifically addressed the relationship between religion and science, I am applying it to the relationship between Intellectual ways of knowing – The Box – and all the other ways of knowing – Outside The Box.

Barbour’s Conflict model of relationship between different ways of knowing is basically aggressive dualism: the notion that only one thing can be right and that the other is not only wrong but irresponsible. This model of relationship often leads to oppression of the non-dominant view and can lead to physical as well as intellectual conflict, and can even result in war and genocide in extreme situations. It is within this model of relationship that the dominant culture insists Intellectual, empirical ways of knowing are the only Real epistemic and pedagogical systems. The result is that other ways of knowing are devalued or even not allowed at all in research, education, the legal system, and meaningful public discourse.

An expression of the Independence model of relationship can be seen in this formal 1984 National Academy of Sciences statement (16) that specifically addresses the relationship between science and religion in the classroom: “Religion and science and separate and mutually exclusive realms of human thought whose presentaiton in the same context leads to misunderstanding of both scientific theory and religious belief.” Independence between other ways of knowing can be summed up by the high school biology teacher who says, “I don’t care if students learn about art — as long as doesn’t happen in my classroom.”

Scholars in the Dialog model focus on process, method, and paradigm. It’s an epistemological issue. And this is where things start to get really interesting. Barbour’s work promoted the idea that religion and science can and should engage in dialogue about their methods, paradigms, and processes. Much of what has since come to be called “the science and religion dialogue” field of scholarship has focused on just that. But in fact what’s compared with science in this field is largely not religion in the larger sense, but the academic field that studies religion — which is theology. And theology, as most humanities, has studiously imitated the methods and processes of scientific inquiry in the pursuit of scholarly credibility. So comparing the methods and epistemic frameworks of science and theology becomes a game that’s really played on just a single court: that of Western science. The epistemologies of both fields are based in materialism, causation, and reductionism even when theoretical physicists bring concepts such as emergence, non-deterministic probability theory, and complexity theory to the table of discourse (17).

Process and Methodology Limits to the Dialogue Model of Integration.

The same epistemic limitation impacts dialogical types of interaction between science and other ways of knowing such as art and literature. The 2013 paper “Reading literary fiction improves Theory of Mind” in the prestigious journal Science presents results of a scientific study of the benefits of reading literature. Authors David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano used an already-established concept called Theory of Mind, or ToM — a skill that allows adults to understand others’ mental states and which therefore greases the wheels of social relationships — as their measuring rod. Their results showed that adults who read literary fiction score higher on tests of ToM (18). But what at first glance seems merely a clever way of assessing the benefit of reading fiction takes on an additional level of significance when the authors discuss the larger meaning of their work. In an NPR interview about the study (19), scientist and co-author David Comer Kidd said: “This study could be a first step toward a better understanding of how the arts influence how we think. We’re having a lot of debates right now about the value of the arts, the value of the humanities. Municipalities are facing budget cuts and there are questions about why are we supporting these libraries. And one thing that’s noticeably absent from a lot of these debates is empirical evidence.” Such a statement, and the assumptions that at least seem to inform it, imply very strongly that empirical evidence is the only meaningful measure that should determine community budget allocations. It further suggests that empirical evidence the only thing that can give literature actual and meaningful value. The authors may not have realized they used Intellectual ways of knowing to literally validate a different way of knowing — in this case, Mythic — but that is what they did. And this is not at all the innocuous thing it may seem to be. Yet it’s very common.

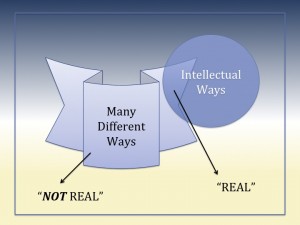

When I was doing a lot of work with the National Science Foundation some years ago, one particular program officer kept trying to get me to develop a program that would test some Diné, or Navajo, medical practices because he was certain they would be confirmed and therefore validated. I wouldn’t do it, and it’s important to understand why. In the image to the right, the banner shape represents the knowledge available from integrating all the different ways of knowing and learning about something in a given situation.

When I was doing a lot of work with the National Science Foundation some years ago, one particular program officer kept trying to get me to develop a program that would test some Diné, or Navajo, medical practices because he was certain they would be confirmed and therefore validated. I wouldn’t do it, and it’s important to understand why. In the image to the right, the banner shape represents the knowledge available from integrating all the different ways of knowing and learning about something in a given situation.

Only part of that field of information comes from Intellectual ways of knowing and learning. We can represent that portion by the area of overlap between the banner, on the left, and a circle that represents Intellectual Ways of Knowing as a whole — about other things, as well as this one thing in question.

Only part of that field of information comes from Intellectual ways of knowing and learning. We can represent that portion by the area of overlap between the banner, on the left, and a circle that represents Intellectual Ways of Knowing as a whole — about other things, as well as this one thing in question.

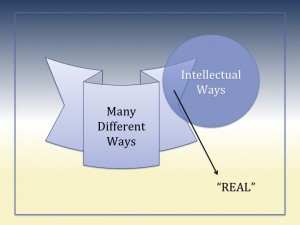

In a dialog model where preferential value is given to empirical evidence, to Intellectual ways of knowing, the area of overlap is now confirmed or validated. This information in that area of overlap is considered REAL. That’s what the NSF program officer wanted to see happen. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with that.

In a dialog model where preferential value is given to empirical evidence, to Intellectual ways of knowing, the area of overlap is now confirmed or validated. This information in that area of overlap is considered REAL. That’s what the NSF program officer wanted to see happen. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with that.

The problem is what happens in the area of the banner that represents information from many different ways of learning, that does not overlap with the circle. This part is not upheld or confirmed by empirical data. So suddenly, as one part is judged to be Real, this whole other part gets judged as NOT Real – and thrown away.

The problem is what happens in the area of the banner that represents information from many different ways of learning, that does not overlap with the circle. This part is not upheld or confirmed by empirical data. So suddenly, as one part is judged to be Real, this whole other part gets judged as NOT Real – and thrown away.

This is the problem with the hidden methodological constraints of the Dialogue model of relationship, however promising it often sounds at first. The Reality that people experience is judged on the basis of specific methodological processes and then redefined in such a way that whole sections of peoples’ life experiences are deemed to be literally “not Real.” Then no further dialogue about them is possible. Further, they cannot be included as “valid” parts of decision-making by either individuals or communities.

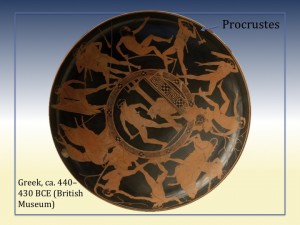

An ancient Greek story tells about a half-god, half-human being named Procrustes who way-laid travelers on the road to present-day Athens and forced them to lie down in his iron bed. Notice the important symbolism of an iron bed, which is rigid and unyielding. Once travelers lay down on the bed, Procrustes made them fit it. If the person was too long and hung off the end of the bed, he whacked their legs off with an axe. If the person was too short and did not fill the bed, he put them on a rack and tore their joints apart to stretch them out appropriately. The people Procrustes met–who were merely passing by, minding their own business–literally had to fit his standard to survive. In the Greek story, a hero named Theseus eventually put Procrustes on his own bed and took care of him. We seem to have no such hero available to us. What we have to do, instead, is watch out for that bed.

An ancient Greek story tells about a half-god, half-human being named Procrustes who way-laid travelers on the road to present-day Athens and forced them to lie down in his iron bed. Notice the important symbolism of an iron bed, which is rigid and unyielding. Once travelers lay down on the bed, Procrustes made them fit it. If the person was too long and hung off the end of the bed, he whacked their legs off with an axe. If the person was too short and did not fill the bed, he put them on a rack and tore their joints apart to stretch them out appropriately. The people Procrustes met–who were merely passing by, minding their own business–literally had to fit his standard to survive. In the Greek story, a hero named Theseus eventually put Procrustes on his own bed and took care of him. We seem to have no such hero available to us. What we have to do, instead, is watch out for that bed.

Its name is assessment.

Assessment as a Process of Acculturation.

Assessment, in our current system, is the tool that reshapes different ways of learning and knowing back to empirical evidence as the only valid way of knowing. When assessment methods must somehow yield empirical data — even if these data are coded narrative responses — it creates a hidden Procrustean bed that cuts off our legs at about the level of our hearts and throws them away. Such assessment acculturates by removing and rendering “not Real” all other ways of knowing. It therefore subtly and powerfully reshapes our concept of Reality to fit that of the dominant academic culture. Please notice that there is nothing at all wrong with including empirical data in our work. What is wrong is excluding every other type of information.

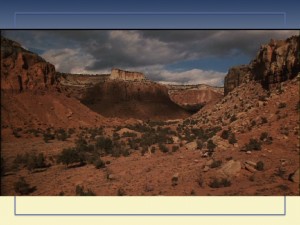

It’s not a coincidence that all the non-Intellectual ways of knowing are overlaid on the landscape and sky in this picture, or that the Intellectual quadrant is laid over the safe little Box that shelters us from seeing all those other parts — or even having to admit that they are there. Fear of the things shown in this image – nature and the full range of understanding that’s available to human beings – are connected in an important way. That movie we’ve been using as a Mythic way of learning about Western culture shows us why in the opening sequence as the credits still play. When you look at the still image of the very short clip, below, it’s nearly impossible to see that there is a human being in the landscape at all. It’s only when you play the clip and there’s motion that the person shows up — dwarfed and overpowered in a way that is intentional.

It’s not a coincidence that all the non-Intellectual ways of knowing are overlaid on the landscape and sky in this picture, or that the Intellectual quadrant is laid over the safe little Box that shelters us from seeing all those other parts — or even having to admit that they are there. Fear of the things shown in this image – nature and the full range of understanding that’s available to human beings – are connected in an important way. That movie we’ve been using as a Mythic way of learning about Western culture shows us why in the opening sequence as the credits still play. When you look at the still image of the very short clip, below, it’s nearly impossible to see that there is a human being in the landscape at all. It’s only when you play the clip and there’s motion that the person shows up — dwarfed and overpowered in a way that is intentional.

(Please click the image below to see the video clip.)

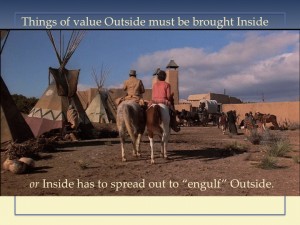

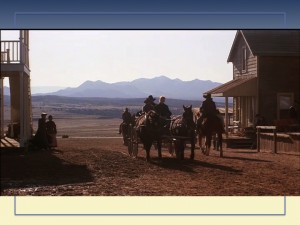

I feel certain at this point that people felt they had to civilize the wilderness for the same reason they feel they need to reshape Indigenous cultural ways of knowing and learning so they are civilized, too. There are two possible ways this can be done. First, things of value Outside the Box can be brought Inside — which acculturates them and makes them safe, as we see in this image from “Silverado” that shows the Fort outpost that surrounds and protects “The Box.” Indigenous ways of knowing, like Indigenous ways in general and the Natural world of which they are a part, lie Outside The Box — in this case, the Fort. It’s important to notice the teepees at its edges of contact with Outside. This particular fort looks more like a trading post and fort combination, which was very common in early contact periods. The trading post provided goods (in exchange for hides and other objects) that drew Native people inside the walls and began to acculturate and “civilize” them. The people who came to trade often camped outside the fort-trading post for extended periods of time as a result.

I feel certain at this point that people felt they had to civilize the wilderness for the same reason they feel they need to reshape Indigenous cultural ways of knowing and learning so they are civilized, too. There are two possible ways this can be done. First, things of value Outside the Box can be brought Inside — which acculturates them and makes them safe, as we see in this image from “Silverado” that shows the Fort outpost that surrounds and protects “The Box.” Indigenous ways of knowing, like Indigenous ways in general and the Natural world of which they are a part, lie Outside The Box — in this case, the Fort. It’s important to notice the teepees at its edges of contact with Outside. This particular fort looks more like a trading post and fort combination, which was very common in early contact periods. The trading post provided goods (in exchange for hides and other objects) that drew Native people inside the walls and began to acculturate and “civilize” them. The people who came to trade often camped outside the fort-trading post for extended periods of time as a result.

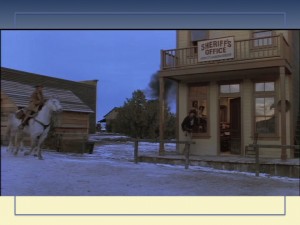

The second step of this strategy is for “The Box” to spread out and engulf “Outside,” which accomplishes the same thing. The entire motif of “pioneering” and “civilizing” expresses these strategies for dealing with ways of knowing, cultures, and nature itself that all lie Outside “The Box” of the dominant culture’s view of Reality. Notice that the picture on the right, also from “Silverado,” shows a more “advanced” stage of civilization in the wilderness, one in which no teepees are visible at all.

The second step of this strategy is for “The Box” to spread out and engulf “Outside,” which accomplishes the same thing. The entire motif of “pioneering” and “civilizing” expresses these strategies for dealing with ways of knowing, cultures, and nature itself that all lie Outside “The Box” of the dominant culture’s view of Reality. Notice that the picture on the right, also from “Silverado,” shows a more “advanced” stage of civilization in the wilderness, one in which no teepees are visible at all.

It is possible for people to escape The Box. But they are not allowed to do so for long. And here is what is important about that statement: it may seem like a personal opinion, but it is in fact information conveyed by the story told in “Silverado” and many other films and books popular in the dominant culture. In the film clip below, we see three of the movie’s heroes escape town on galloping horses, one of them whooping with glee. In this case, the town represents a part of civilization that literally wants to not only imprison these men but execute some of them. Then a posse thunders out in pursuit of them, to bring them back. I have added a voice-over that identifies the pursuing mythic enforcers here with elements of the real world that play the same role with respect to educators who dare to escape The Box of Intellectual ways of knowing.

(Please click the image below to see the video clip.)

We can’t stop the “posse” — whether it’s a tenure committee, school board, state legislature, or scholars from the research community — from coming after those of us who escape The Box. But we can convince them to change the way they see it when we get away. It’s not that what we’re doing isn’t Real, though that is often how they judge the situation, thereby rendering what we do as literally meaningless. Instead, we simply cross the boundary of “Real” as it’s defined by the dominant culture. Yet another clip from “Silverado” illustrates even this point of view, one that’s undoubtedly achingly familiar to many of the (non-academic, after all!) artists who write, produce, and act in films. The very short scene below takes place when the posse seen above finally catches up with the escapees and is met by resistance.

(Please click the image below to see the video clip.)

The pursuing sheriff’s realization is actually appropriate. Because when you reach that boundary between “inside the box” and what’s outside, it’s simply the end of a certain type of jurisdiction – NOT the place where Reality itself ends. I’m not advocating that we resist being taken back Inside through violent means. But I am advocating a rewrite of our own understanding of what it means to escape, and of the nature of the landscape we then inhabit.

Genuine Integration of Different Ways of Knowing Requires A New Model for Education and Learning Assessment.

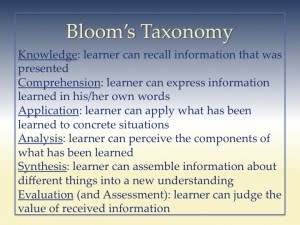

Now we can return to Barbour’s last category of relationship between religion and science, which is Integration. In terms of different ways of knowing and learning, I would suggest it’s not possible to integrate the ways of learning and knowing if three of the four — Experiential, Spiritual, and Mythic — are literally disallowed as “not Real.” But they’ve been disallowed for so long that people in contemporary culture are literally ignorant about these other ways of knowing and learning or how to use and assess them. You can think about it in a Bloom’s taxonomy way, remembering that the higher cognitive levels require opportunities to learn at lower levels first and that application and assessment are high-level cognitive skills (20).

Because contemporary academia does not recognize Experiential, Spiritual, or Mythic ways of knowing as valid, these ways of knowing are not addressed in schools or informal learning environments. So while students learn how to handle information acquired through Intellectual ways of knowing at ever higher cognitive levels as they go through school, they remain ignorant about how to use or assess information acquired through these other means. The results of their ignorance can be literally lethal when someone who professes to “teach” information acquired through Spiritual Ways of Knowing (for example) does not, in fact, know what they are doing. This is how self-proclaimed “sweatlodge gurus” who charge people thousands of dollars for rituals find themselves in situations where their “learners” have died from hyperthermia and dehydration. The problem is not that Spiritual ways of knowing are bogus; it’s that neither the self-proclaimed teachers or the paying learners from the dominant culture have any idea how this type of learning works. Because it’s been ruled “not Real” they have no chance to learn it as they grow up. When people do not learn how to analyze information from different ways of knowing, they can only take whatever is presented to them at face value, believing whatever is communicated. That’s what makes both propaganda and advertising possible — and lucrative.

How can we teach the equivalent of “critical thinking” skills that use and assess information acquired through Experiential, Spiritual, and Mythic ways of learning and knowing? Some people are trying. The ReNEW Cultural Arts Academy of New Orleans (now part of ReNew Schools) has integrated the arts into its curriculum in a way that renewed the interest of at-risk students in learning. A CBS news report on the school, however, demonstrates the role of Intellectual ways of knowing in assessing the validity and effectiveness of such a program. For example, the fact that “the school has seen a 20 point rise in standardized test [score]s over five years” is cited as evidence of the program’s success. Further, Principle Ron Gubitz is quoted as saying the goal of the school’s curriculum “. . . is actually to use the music and the visual arts and use theater to teach core content” — “core content” referring to state education standards in subjects such as math and science — and then we are given substantiating examples such as “students count the measures in band or stand up in math class to act out a bar graph.” There is nothing wrong with any of this. But there’s a lot more right about such a curriculum than is “validated” by these measures. If we can’t assess what’s going on in other areas, though, or if they cannot be “demonstrated” to the public, this kind of program is historically discontinued as inefficient — too expensive for the outcomes achieved. No one notices that there are essential outcomes achieved that are simply not being measured or seen at all. Yet those are the outcomes that create wholly educated people.

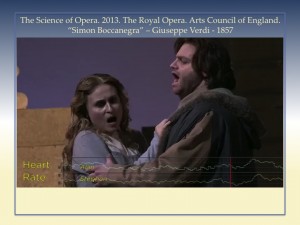

Here’s another example of a study seeking to assess Mythic ways of knowing, in this case what people learn through music and theater. In 2013, the Royal Opera, the Arts Council of England, and science faculty from University College London teamed up to produce the public education film “The Science of Opera.” The film was set up to study the impact of the arts and also show the public that the arts are, in fact, important. (The quotes from Trimble about human biological responses to music, cited earlier, are from this film.) Several neuroscientists of different types wired up British television personalities Stephen Fry and Alan Davies with sensors that would record their heart rates, body temperatures, and respiration rates, and then recorded what happened while they watched the Verdi opera “Simon Boccanegra.” Fry is an avowed opera buff, whereas Davies had never seen one before. A very brief segment showing some of the results is shown in the video clip below. There are three things to notice: (1) the way the viewers’ heart rates change over time (watch the scrolling red vertical line that crosses the heart rate recordings for each man to show “this is the heart rate now, at this moment”); (2) how those changes in heart rate relate to the music being played in the production at those moments (audible on the sound track; the climax of the music coincides with the plot’s emotional climax); and (3) the visual expressions and whole-body affect of both men, and how those compare to the changes in their recorded heart rates (at the same time).

(Please click the image below to see the video clip.)

The music clearly impacted heart rate in both the opera afficianado and the opera newby, and in remarkably similar ways. That’s significant. But what I find even more significant is the dissonance between what happens to these people physiologically and the visible affect they display. Looking at them, you would never guess they were engaged with the music or production; they look not only bored but almost catatonic. Yet both men said they enjoyed the opera — and their heart rates (and other measures not shown in this brief clip) clearly show they were deeply engaged in what was going on. If they hadn’t been wired to recording devices, however, we’d never have known there was such a huge level of invisible but powerful response going on.

What does this mean about the ways we assess our own students’ levels of engagement in specific learning environments? It’s common in philosophy of science to note that what we observe is limited by our means of observing it; new tools open up new fields of information. Physiological measures of the men watching an opera show us that something was going on, but we still really don’t know what it was. What kinds of assessment methods would tell us that the expressions we see here are ones of rapt attention or processing rather than boredom? What means of assessment could tell us what these men learned from this experience, or even that they learned something, or how the experience impacted them? Intellectual ways of knowing and empirical data cannot really assess what’s learned through Mythic ways of knowing. They can only show us that something is happening outside the reach of our measuring systems.

Next Steps: An Overview and an Example of Exploration.

So how can we proceed? I would propose that we need to find out what people learn through Experiential, Spiritual, and Mythic ways of knowing, and how they learn it. To do this, we need to consider several key questions:

- What are the outcomes for these kinds of learning and knowing?

- How would you know a learner had achieved those outcomes?

- What are the processes of learning in these non-cognitive ways?

- Do the processes of learning in these ways have steps? If so, what are they? (This would generate a non-cognitive “Bloom’s taxonomy” of such learning.)

- How are the processes of learning in these ways unique? And how do those processes relate to the non-cognitive “Bloom’s taxonomy” steps?

- What are typical “derailings” and stumbling blocks to learning in these ways? How do we recognize them?

- How can such a learning journey be assessed?

So . . . how can we DO this? We have to go into that landscape of Outside. That’s where those kinds of learning exist, so we cannot address such questions from Inside The Box.

When we do start this work, I can think of two things we can meaningfully search for. The first is mentors. We need to (1) identify people who are skilled in Experiential, Spiritual, and Mythic ways of knowing; (2) find out which of these pass on their knowledge to others by mentoring or teaching; and then (3) ask with authentic respect if they will teach us what they do as teachers in these ways of knowing. Notice: We don’t mine them for the information we want and then write a paper about it. We sit down and let them teach us as people who know things we don’t.

The second thing we can do is research to learn basic information: (1) WHAT do people learn through Experiential, Spiritual, and Mythic ways of knowing? and (2) HOW do they do it?

I’ve tried my hand at research that might start to address these questions off and on since about 1995. Nothing is published because, frankly, I don’t think it can be. I was just struggling to understand Experiential, Spiritual, and particularly Mythic ways of learning because it’s important to me. It’s important to note that, in doing this work, I assumed that people in Western culture learn the same ways Indigenous people do. There’s reason, after all, to believe Western culture values these other ways of knowing — however much it officially denies it — because it HAS music, art, and cathedrals. And it produces movies like “Silverado,” in which the audience does not watch the heroes escaping town and yell to the pursing posse: “Get ‘em! Yeah! Hunt ‘em down and bring ‘em back!”

In fact, movies like “Silverado” suggest to me that people of the dominant culture really want to escape, to go Outside The Box — whether in nature or ways of knowing. But they’re trapped in The Box by their fears.

In fact, movies like “Silverado” suggest to me that people of the dominant culture really want to escape, to go Outside The Box — whether in nature or ways of knowing. But they’re trapped in The Box by their fears.

So given that it seems to me all people learn in all these different ways, I used online populations of mixed culture (mostly dominant culture but with some individuals from marginalized cultures) for my research. Here is just one example of the kinds of things I learned. I share in hopes it may help prime the pump of our thoughts about how to proceed in the future.

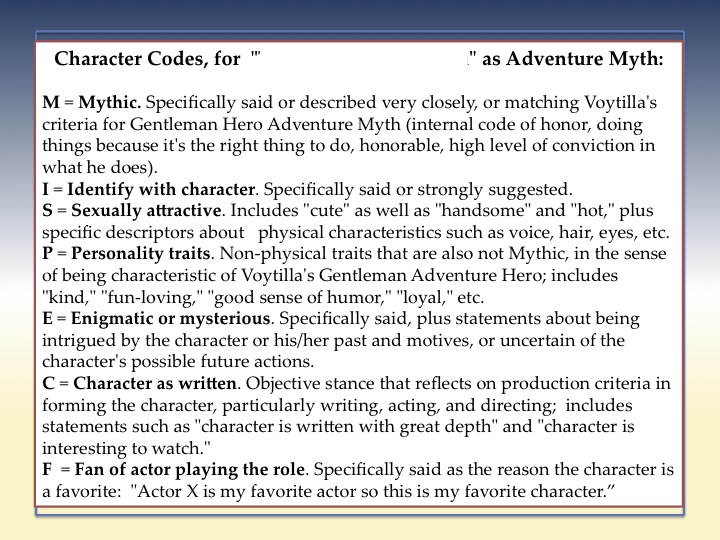

One of the projects I carried out was a detailed research survey of a single television program’s online fan base, to explore how learning through received story is connected to other kinds of learning such as that from dreams, imagination, stories the fans themselves write, and the things they value enough to talk about with others. I chose a program that had nearly ten regular characters who shared largely equal air time, but that had a fairly limited number of episodes to analyze. The survey collected basic demographic information and then asked fans about their favorite characters and why those were favorites, their favorite episodes and why they were favorites, their favorite fanfiction stories (both read and written) and why they were favorites, accounts of dreams and daydreams that involved characters from the program, and who they talked with about the program and what they discussed. Then I used contingency table analysis on the coded narrative responses to map character features against story features of aired episodes, fanfiction, dreams, and daydreams to see what it might tell me about what people were perceiving in story.

I picked several standard European cultural Myths from published literature (since the program’s writers and producers were British nationals and White Americans) that seemed to apply to the program, and then simply tried out various ways of coding storyline and character narratives for each Myth (one person might be a Hero in a certain type of story but a Trickster in another), to see if the data would fall into a coherent pattern where story and character fit one another. My thought was that if all the variables “fell out” into a recognizable pattern, it would show me what it was the viewers were perceiving.

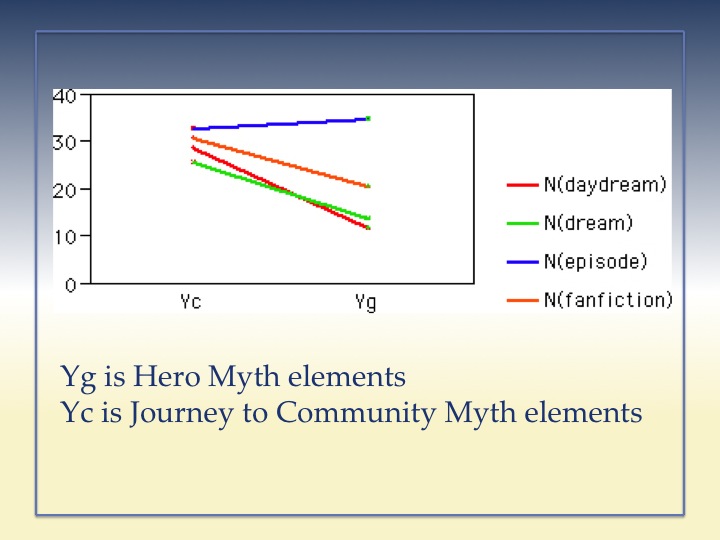

And here’s a example of the kind of thing I saw, that interested me. This graph plots how elements of two prominent myths played out in fans’ reports of aired episodes, fanfiction, dreams, and daydreams. The two myths are “Journey to Community” (Yc on the x axis) and Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” (Yg on the x axis). Over each myth area of Yc and Yg, four points show what percent (y axis) of the more than 800 respondents mentioned facets of the Journey to Community Myth or the Hero Myth as important in their favorite televised episode, fanfiction, dream, or daydream. Four lines connect the points of “importance” for each vehicle (episode, fanfiction, dream, and daydream) in the two Myths so it’s easier to see how they compare.

And here’s a example of the kind of thing I saw, that interested me. This graph plots how elements of two prominent myths played out in fans’ reports of aired episodes, fanfiction, dreams, and daydreams. The two myths are “Journey to Community” (Yc on the x axis) and Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” (Yg on the x axis). Over each myth area of Yc and Yg, four points show what percent (y axis) of the more than 800 respondents mentioned facets of the Journey to Community Myth or the Hero Myth as important in their favorite televised episode, fanfiction, dream, or daydream. Four lines connect the points of “importance” for each vehicle (episode, fanfiction, dream, and daydream) in the two Myths so it’s easier to see how they compare.

The blue line shows what proportion of viewers perceived the Hero Myth or Journey to Community Myth in televised episodes: it’s between 30 and 40%, slightly higher for Hero than Community (meaning more viewers perceived the Hero Myth in televised episodes than perceived the Journey to Community Myth in those episodes). Both myths were perceived less commonly in fanfiction, dreams, and daydreams than in the televised episodes: the points for each are successively lower on the y axis (down to about 10% for the perception of Hero Myth in fanfiction [the point where the red line “hits” the dot above the Yg label]). Interestingly, the orange, green, and red lines show us that viewer perception of the Hero Myth dropped far more in fanfiction, dream, and daydream than did viewer perception of Journey to Community in the same three kinds of stories. That is to say, fans’ favorite fanfiction stories and the stories that played out in their sleeping dreams and waking daydreams expressed Journey to Community Mythic elements only a little less frequently than those elements were perceived in the aired episodes (down from about 33% for aired episodes to a low of about 25% for dreams). But the Hero Myth was perceived much less frequently in fans’ favorite fanfiction, dreams, and daydreams than in the aired episodes; all three lines drop fairly steeply from Yc to Yg. This is despite the fact that fans clearly perceived the Hero Myth in their favorite aired episodes (the highest percentage of respondents, at about 37%).

Many Postmodernist scholars say that what people see in a story is projected or constructed, not actually there. More Modernist views of literature see legitimate meaning as solely what’s been structured into the story by the writer or teller. I think these data suggests that both things happen and that, in fact, the relationship between people and Story is richer and more complex than either model suggests.

First, projection cannot explain the pattern of Hero Myth perception in the different kinds of stories. It looks very much like the pressure of the televised episodes every week pulled the Hero level in the fans’ fanfiction stories up towards the aired episode level. Please notice that the Yg point (Hero Myth) on the orange line that shows the frequency of a perceived Myth in favorite fanfiction is just about half-way between the values for dream and daydream (on the green and red lines), and aired episodes (blue line). If the fans are projecting the Hero Myth elements from within themselves, these four points should all be very close to each other. It seems reasonable, in fact, to think they would all lie at about the level seen in fans’ daydreams, since we know that’s coming from an internal source. But instead we see that although only about 12% of the fans perceived the Hero Myth in their dreams and daydreams, more than 35% of them perceived the Hero Myth in the aired episodes of the program. And I think it seems very unlikely they could have projected something into the aired episodes that wasn’t playing out in their own internal stories. So these data seem to me to support the idea that story is not projected but perceived. After seeing these data, I asked the producers about the program and learned that they had intentionally structured its storylines using Campbell’s Hero Myth.

At the same time, the fans perceived a Journey to Community Myth in the aired episodes that the producers were not (at least consciously) aware of structuring into their production. The fact that the pattern of perception for this story is very similar across all four venues (aired episodes, fanfiction, dreams, and daydreams), and that it was far more common in the fan-generated venues than was the Hero Myth, further suggests that this story may have been coming from the fans themselves and was projected onto the aired episodes. This suggests a rather interesting scenario in which the fans’ perceptions of the Hero Myth being told in the televised episodes was correct, and they internalized that story into their fanfiction to some degree, and less so into their far more personal dreams and daydreams. But when it came time to tell their own stories about the characters in dream, daydream, and fanfiction, the viewers largely abandoned the Hero story in favor of the Journey to Community story they liked better. Then they projected that story into the aired episodes.

This study does not tell us yet, of course, how people learn from story. But it’s a start to thinking about how we might approach understanding this. And, as we begin to approach this kind of exploration, we need to incorporate Indigenous views of story that differ from the Modernist and Postmodernist views just discussed. In the latter, story is created by human minds. This is true whether the human involved is the writer / teller or reader / listener. In Indigenous worldview, really important stories tell themselves.

Procrustes in the Land Between the Mountain and the Sea.

So now I’m going to shift gears and finish the story about Procrustes I began earlier in this presentation. Because there’s a Story telling itself here that really should matter to us, as educators.

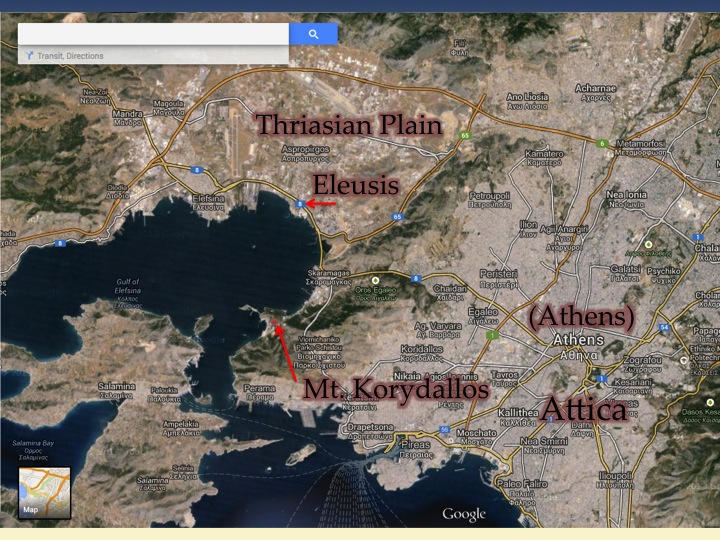

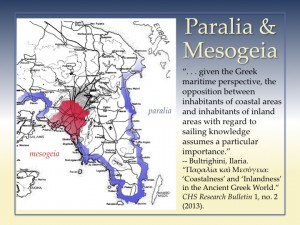

The area where Procrustes put his iron bed was in what is now the country of Greece, near Attica (the area circled on this map). Theseus, the hero who killed Procrustes, started his journey to Attica in Troezen (labeled in large letters) and walked around the bay that lies between them.

Procrustes had his camp set up on the Via Sacra, a holy road that ran from Attica to Eleusius – a very sacred site to the ancient Greeks. The road went through a pass (indicated by a red arrow on the map below), at the base of Mt. Korydallos, and along the narrow strip of land between the mountains and the sea. That’s why Procrustes could nab people. They had to go past him on this narrow road. Take a moment to familiarize yourself a little with the features labeled in red and black letters on this map.

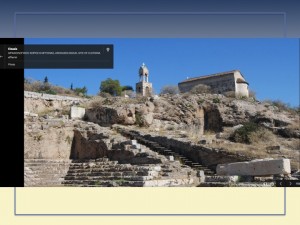

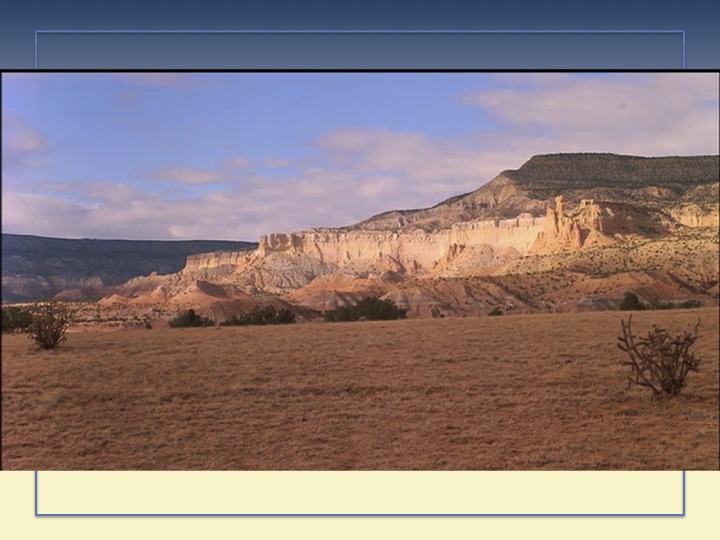

Here’s what the Thriasian Plain looked like in 1907 (right). You can see the ruins of Eleusius (in particular one of the small white buildings) off on the far left side of the image, in the background. The photograph below left shows what those same ruins at Eleusius look like today, from much closer of course.

Now. Two things are noteworthy. First, the mountains on the road in question are not all that impassable. Here’s a view (below right) from that area near Mt. Korydallos, looking towards Athens, which was founded in Attica. So travelers could have hiked around Procrustes. It was an option.

Now. Two things are noteworthy. First, the mountains on the road in question are not all that impassable. Here’s a view (below right) from that area near Mt. Korydallos, looking towards Athens, which was founded in Attica. So travelers could have hiked around Procrustes. It was an option.

Travelers could also have sailed around Procrustes. The ancient Greeks divided themselves into populations designated by names that described whether they were inland-dwellers or coastal sea-goers (23). The mesogeia people of Attica were the ones walking to Eleusius, right through an area where the paralia locals got in a boat and sailed down the coast to go somewhere. I’m sure the people of Attica felt that walking on the Via Sacra was much safer than hiking over the mountains, and certainly safer than setting to sea in a boat they didn’t have the skills to sail. But in point of fact, it was deadly. Not safe. The restrictions on how far they were willing to venture off the beaten path made it possible for Procrustes to do what he did to them. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have been there. He’d have been all alone, dangling his feet off the side of that iron bed.

The second thing that’s noteworthy is that Theseus founded Athens. You are no doubt aware of the associations between classical Western education and Athens. There’s a reason so many old universities have Greek columns on their administration buildings. So this road, the Via Sacra, connected the seat of education and culture with a high holy site. It allowed people to go from one place to the other, however restricted the means of access might be.

Stories transmit important information, and that’s true of stories from ancient Greece as well as ones we see in movies today. Pause to consider for a moment the connection being drawn here, literally along the Via Sacra (“Sacred Road”), between the city that became Athens and an extremely sacred site, a man with an iron bed he made people fit, and the man who founded a cultural center we still associate with education.

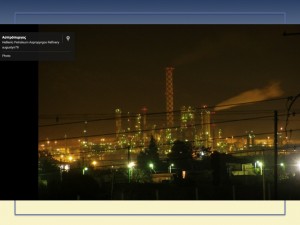

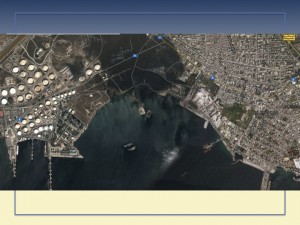

Here is what Eleusius looks like today (right). It’s that little spot of green, there, center of the right half of the picture on the right. Obviously, it’s very ancient and in ruins. You can see the Thriasian Plain all around it – a very heavily industrialized area today. There are oil refineries in the left half of the picture, for instance. Below left, you see a picture of what this area looks like today at night.

Here is what Eleusius looks like today (right). It’s that little spot of green, there, center of the right half of the picture on the right. Obviously, it’s very ancient and in ruins. You can see the Thriasian Plain all around it – a very heavily industrialized area today. There are oil refineries in the left half of the picture, for instance. Below left, you see a picture of what this area looks like today at night.

Somehow, having a safe road between a sacred place and the seat of learning did not work out to be all that safe, or to protect anything at all. We need to think about this very seriously.

Story tells us things.

Finale.

In closing, I want to give you a last bit of Mythic Knowing as something of a gift: a 40-second clip from – yes! – “Silverado.” It’s loaded up with the power inherent in story, music, landscape, and even ritual, and it tells us a story about daring to ride into the landscape of Outside. It also demonstrates more completely than anything I can write (Intellectual learning!) how powerful is the full range of different ways of knowing and learning. It’s also my hope that the story told in this clip will lift you and carry you a good long way on your journey. Because the journey you are on is one that matters to us ALL.

(Please click the image below to see the video clip.)

References, Notes, and Media Credits

*Original url for this paper was http://tapestryinstitute.org/occasional-papers/assessment-as-acculturation-vol-1-no-2-may-2015. That link now redirects to this page.

* Important note: This paper was written in 2015, before Tapestry began to take a stand against the use of the term “Western culture” to refer to what is actually Western worldview. The information in the linked page explains why the term “Western culture” is actually without real meaning. Because the most commonly used term is “Western culture,” and because Western scholars are resistant to changing it, Tapestry used a variety of terms for this aspect of the dominant worldview, in various combinations, for many years. In 2025, we got to the point in our own work of creating collaborative relationships with Western funders that we simply had to not only clarify this terminology problem, but change our own usage in our papers and call attention to it in the larger community. Terms such as “Western culture,” “the dominant culture,” “modern culture,” and “contemporary culture” therefore appear from time to time in this entire article. We have left those terms in place because of the published nature of this work. To correct the problem, we added this note instead, on 7.24.2025.

1. “Silverado.” 1985. Lawrence Kasdan,Director. Lawrence Kasdan and Mark Kasdan, Writers. Columbia Pictures, Delphi III Productions.

2. N. Scott Momaday. 1969. The Way to Rainy Mountain. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. p. 4.

3. Diagrams on this slide are from http://tapestryinstitute.org/ways-of-knowing/intellectual/tornadoes. The Doppler radar image is used with permission from the National Severe Storms lab (see http://tapestryinstitute.org/ways-of-knowing/intellectual/tornadoes/doppler for details). The cloud diagram is by Dawn Hill Adams, Ph.D.

4. Tornado video clip is from a storm near Attica, KS in May 2004. Video by Martin Lisius, StormStock, Prairie Pictures Inc. SM20040512. Stormstock.com.

5. “The Science of Opera” with Stephen Fry and Alan Davies, 2013. The Royal Opera. Arts Council of England and University College London.

6. Lois and Essary Jacka. 1994. Enduring Traditions: Art of the Navajo. Northland Pub.

7. “Cave of Forgotten Dreams.” 2010. Werner Herzog, Director. Werner Heron, Writer. Creative Differences, History Films, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Arte France (co-production), Werner Herzog Filmproduktion (co-production), in association with More4.

8. Animation in Paleolithic art: a pre-echo of cinema. Marc Azéma and Florent Rivère. Antiquity / Volume 86 / Issue 332 / January 2012, pp 316 – 324.

9. “The Science of Opera,” op. cit.

10. “Oklahoma.” 1955. Fred Zinnemann, Director. Sonya Levien, William Ludwig, Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II, and Lynn Riggs, Writers. Magna Theatre Corporation and Rodgers & Hammerstein Productions.

11. Daniel Goleman. 2004. Destructive Emotions: How Can We Overcome Them?: A Scientific Dialogue with the Dalai Lama. Bantam. page 316. Original research published in F. Varela, J.-P. Lachaux, E. Rodriguez, and J. Martinerie, “The Brainweb: Phase Synchronization and Large-Scale Integration.” Nature Reviews: Neuroscience 2 (2001): 229-39.

12. C. Brown and P. Hagoort. 1993. The processing nature of the N400: Evidence from masked priming. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 5(1):34-44.

13. Jeremy R. Gray, Todd S. Braver, and Marcus E. Raichle. 2002. Integration of emotion and cognition in the lateral prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99(6):4115-4120.

14. C.P. Snow. 1959. The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. The Rede Lecture 1959. Cambridge University Press, New York. Available online at http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/students/envs_5110/snow_1959.pdf

15. Ian Barbour. 1966. Issues in Science and Religion. Prentice Hall, New York.

16. National Academy of Sciences. 2008. Science, Evolution, and Creationism. Washington, D.C. National Academy of Sciences Press. page 47

17. Statements about the nature of epistemic comparisons in the science and religion dialogue field of scholarship are based on my professional experience. During the 1990s, I was Southwest Regional Director of the Templeton Science and Religion Course Program, a judge in that program’s international course competition, and a frequent faculty presenter on the discipline of “science-and-religion dialogue” at instructional workshops for university and seminary faculty at institutions across the U.S. I served on a AAAS Science and Religion dialogue panel in Washington, D.C., organized several national conferences and workshops on the subject, and won an award for outstanding teaching of science and religion from the John Templeton Foundation. I knew Ian Barbour personally and held him in the highest esteem. I found it meaningful, however, that even members of the Society of Ordained Scientists struggled to bring Spiritual ways of knowing — as opposed to academically-based theological ways of knowing — to the conversation. This is not due to any personal or professional shortcomings on the parts of the scholars involved, but seems to me a natural outcome of the entire dialogue being situated within the worldview of Western academic scholarship. When I raised this issue with several key leaders in the field, they explained that anything “less” (an interesting choice of words) would damage the field’s academic credibility. In other words, assessment is a limiting factor for this discipline as it is for so many other things. That the rules of a “creditable” epistemic system impose limitations on valid and acceptable methods, processes, and paradigms for the science-and-religion dialogue, and that these limitations largely exclude non-theological aspects of religion from the field of acceptable discourse, is deeply ironic.

18. David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano, “Reading literary fiction improves Theory of Mind,” Science, published online October 3, 2013, doi:10.1126/science.1239918.

19. Nell Greenfield Boyce, “Want To Read Others’ Thoughts? Try Reading Literary Fiction,“ NPR, October 14, 2013, http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2013/10/04/229190837/want-to-read-others-thoughts-try-reading-literary-fiction.

20. Benjamin Bloom et al. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Longman, Green. New York. An excellent summary of Bloom’s original taxonomy and subsequent revisions is available online at the Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching, http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

21. Michelle Miller. May 20, 2014. “Arts turn around troubled New Orleans school.” CBS News. Available online at http://www.cbsnews.com/news/arts-turn-around-troubled-new-orleans-school/

22. Joseph Campbell. 1972. The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

23. Bultrighini, Ilaria. “Παραλία καì Μεσόγεια: ‘Coastalness’ and ‘Inlandness’ in the Ancient Greek World.” CHS Research Bulletin 1, no. 2 (2013).

© 2015 Tapestry Institute. All Rights Reserved.