We just spent the weekend at the Rocky Mountain Horse Expo in Denver, where we were doing a bit of fund-raising for the sessions of Itahoba Horse for adult survivors of sexual assault. As we sat there one day, a couple of fellows came by to “educate” us about mustangs. They announced themselves as being from a strictly apolitical group, whose interest was solely in finding homes for mustangs so as to take care of “the mustang problem”. (I won’t name the organization, but it works so closely with the Bureau of Land Management that the BLM logo is on their business card.) These men were going from table to table providing “factual” information about mustangs to folks. And chief among these facts was that mustangs were not really around before the Great Depression, but are primarily the product of ranchers and farmers turning loose or setting free the stock they could no longer feed during the 1930s.

Maybe it’s because I’m a scientist. Or maybe it’s the Choctaw in me. But I have a hard time with people who go from table to table to spread a supposedly non-political message that is in fact based on lies. Because there is a very long historical record of mustangs being in the American West in large numbers long before the Great Depression. I want to point out just a few of them here.

The Texas State Historical Association reports that on July 10, 1839 (yes, 1839, not 1939), the Little Rock Arkansas Gazette printed the following: “The mustang or wild horse is certainly the greatest curiosity to those unaccustomed to the sight, that we meet with upon the prairies of Texas. They are seen in vast numbers, and are often times of exceeding beauty. The spectator is compelled to stand in amazement, and contemplate this noble animal, as he bounds over the earth, with the conscious pride of freedom. We still meet with many in the lower counties, and during the summer hundreds were seen in the neighborhood of Houston, darting over the plains, and seeming to dare the sportsman for a contest in the chase.”

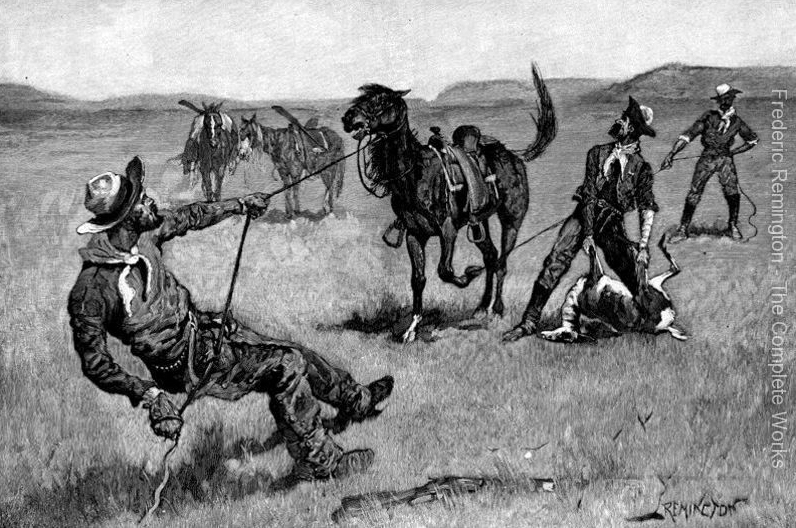

This particular entry in the TSHA’s Online Handbook of facts about Texas history goes on to say that “The number of mustangs were impressive. Just before the Mexican War [note: 1846] Lt. Ulysses S. Grant, while with Gen. Zachary Taylor’s army on the Nueces River, stated, ‘I have no idea that they could all have been corralled in the state of Rhode Island, or Delaware, at one time.'” It cites an admiring passage about mustangs by the great Western artist Frederic Remington, who lived from 1861 to 1909 and therefore died long before the 1929 onset of the Great Depression. That’s one of Remington’s depictions of mustangs, painted about 1890, just to the left of this paragraph.

Historical literature of the American West, especially Texas, is literally filled with descriptions of mustangs. They were caught and tamed, sometimes hunted as game, and often the subject of irate diary or journal entries after they ran off strings of domesticated stock. As an example, one of the more well-known books of early Texas history is “The Evolution of a State” by Noah Smithwick, who came to what is now Texas in 1827 as a strapping 19 year old. Smithwick lived into his 90s, and in 1900 the Gammel Book Company of Austin published his memoirs. Mustangs were so ubiquitous to Texas life that he wrote of them very casually, telling in one story about the adventure that ensued after he traded his own horse to “Joe McCoy, the famous mustang catcher” for a black mustang mare. Obviously there could not have been such a thing as a “famous mustang catcher” before 1840 if mustangs only showed up a hundred years after that.

Even Zane Grey, the prolific author whose works are sometimes seen as somewhat fictional representations of the West, documents the presence of mustang herds well before the Depression. They appear in many of his books, and one of his later novels is titled “Wild Horse Mesa” — published in 1928. Whatever you might think of Grey’s ability to accurately represent the West, he certainly could not have imagined and written about wild horses in large numbers more than a decade before they supposedly came into existence.

Mustangs are certainly a political issue, there’s no denying it. And I am not going to tell you I have a solution. More to the point, I’m not sure one is necessary. In all honesty, it hasn’t been that long since people were in a lather over what to do about “the Indian problem.” As a person whose family was deeply engaged in that, I can say many Indians feel like the problem wasn’t one the Indians had. We saw it as a whole different kind of problem. I sometimes wonder if the mustangs don’t see things the same way.

The point is, historical information about mustangs comes from many different sources, including art and story because artists and storytellers record and reflect on the things they see and experience. In this case, though, we have numerous types of historical data as well, ranging from the journals of early explorers and Spanish padres to accounts such as that from Grant’s autobiography. In light of all that information, it’s puzzling that people who work closely with those in charge of mustang roundup and adoption would try to rewrite the story in such a large way. Of course, this kind of rewriting is common in cultures facing enormous paradigm shifts, though when that happens such rewrites are not at all apolitical.

Whatever the reason for the tale these men were telling — and they went from one exhibitor’s table to another, diligently educating person after person and counting on the politeness of their hearers to protect them from embarrassment — it seems appropriate to at least lay out some of the information that puts the lie to the particular story they were telling. Whether mustangs should or can remain in the wild is immaterial at this point simply because the wild itself is vanishing. But rewriting the mustangs’ history to say they weren’t in existence before 1929 is as unnecessary as it is untrue. They are what they are, and it doesn’t hurt anyone to let the mustangs retain their honorable identity. It might make the people removing them from the wild feel a little less guilty — but that’s never been a good reason to rewrite history.